A Life Shaped by Work, Family, and the Spirit of Liverpool

Edward Christopher Roach was the maternal grandfather of my wife, Sarah — her mother’s father — and part of a proud Liverpool family whose story reflects the strength, endurance, and quiet dignity of Britain’s 20th-century working class. His life spanned from the First World War to the final years of the 1980s, a period that saw immense social and industrial change in Britain. Through those decades, Edward built a life grounded in hard work, family loyalty, and the unspoken resilience that characterised Liverpool’s dockside communities.

Early Life in Wartime Liverpool

Edward Christopher Roach was born in Liverpool in 1916, during the middle of the First World War. Britain was under strain, with much of the nation’s male workforce serving abroad and those at home keeping the industrial heart of the country running. Liverpool, one of the busiest ports in the world, played a crucial role in the war effort — its docks handling supplies, munitions, and food shipments essential to Britain’s survival.

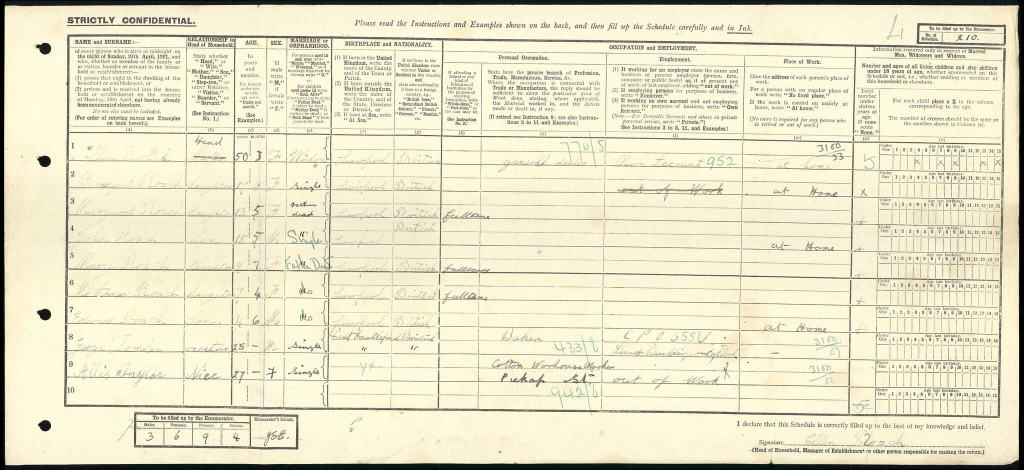

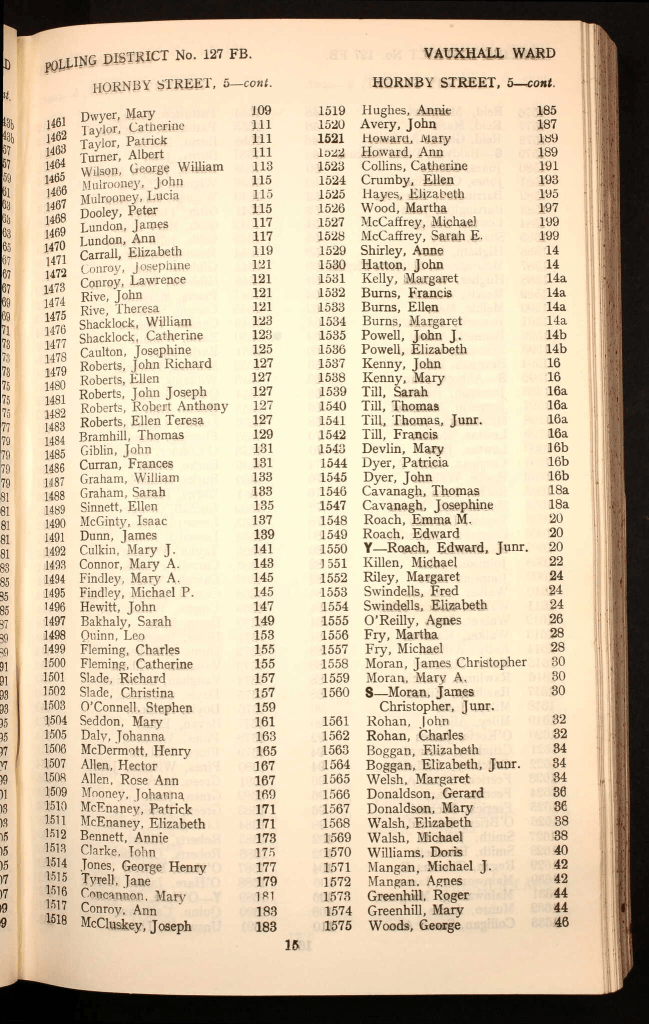

The Roach family belonged to the city’s working class, part of the great industrial tide that powered Liverpool’s growth through the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Census records from 1921 show Edward living in the city as a young child, surrounded by the bustle and hardship of post-war reconstruction. The Liverpool of his early years was a city marked by overcrowded housing, fluctuating employment, and strong community spirit — where street life, neighbours, and family provided stability when work could not.

The surname Roach has Norman roots, derived from the Old French roche, meaning “rock” or “cliff.” It’s a name that became common across Lancashire and Merseyside, where generations of Roach families worked in docks, shipyards, and factories. For Edward, this heritage linked him to centuries of settlement and labour in the north-west of England — a lineage defined by endurance, practical skill, and community belonging.

Marriage to Emma Burke

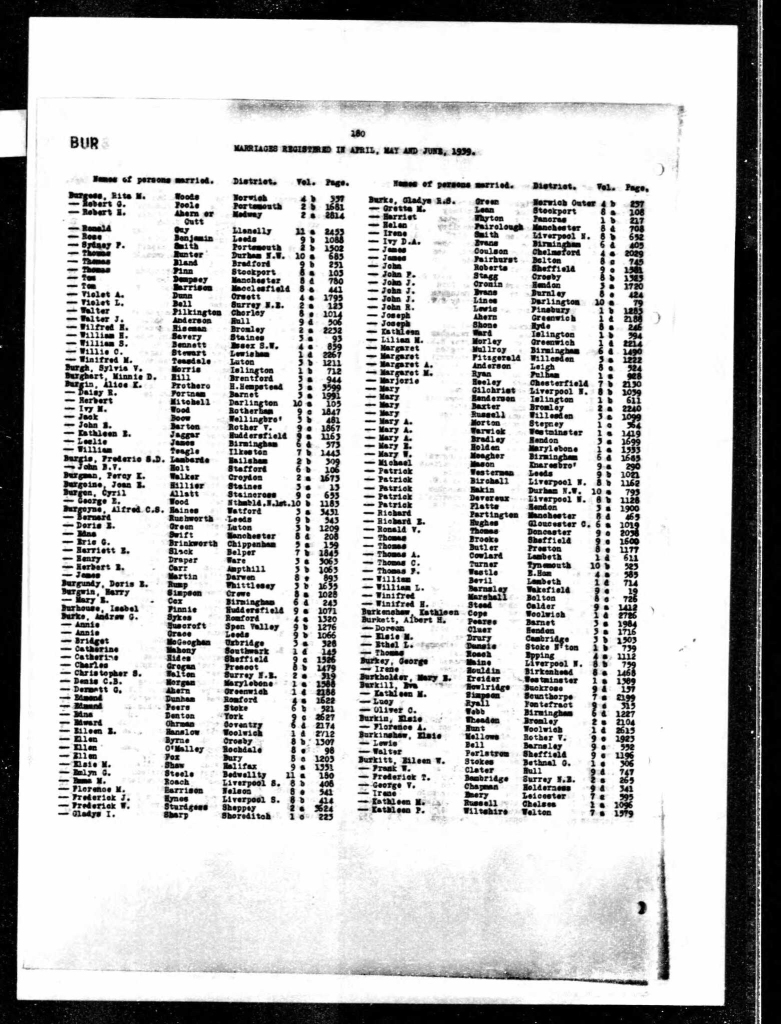

In the mid-1930s, Edward married Emma M. Burke, marking the start of a partnership that would last for more than half a century. The marriage took place in 1938, a time when Britain was slowly recovering from the Great Depression.

Emma’s background added a rich thread to the family story. The Burke surname was strongly associated with Liverpool’s Irish Catholic population, whose ancestors had arrived in vast numbers during the 19th century to escape famine and poverty in Ireland. By the time Edward and Emma married, intermarriage between long-settled English and Irish families was commonplace in Liverpool, blending traditions and faiths into a distinctive local identity.

Their marriage was a product of its time — two young people seeking stability, hope, and partnership in a city still feeling the aftershocks of economic hardship. They built a family that endured through war, reconstruction, and the social transformations of post-war Britain. Over the next five decades, they raised six children and established a family home that would become a lasting centre of love, humour, and belonging.

Working Life: The General Labourer

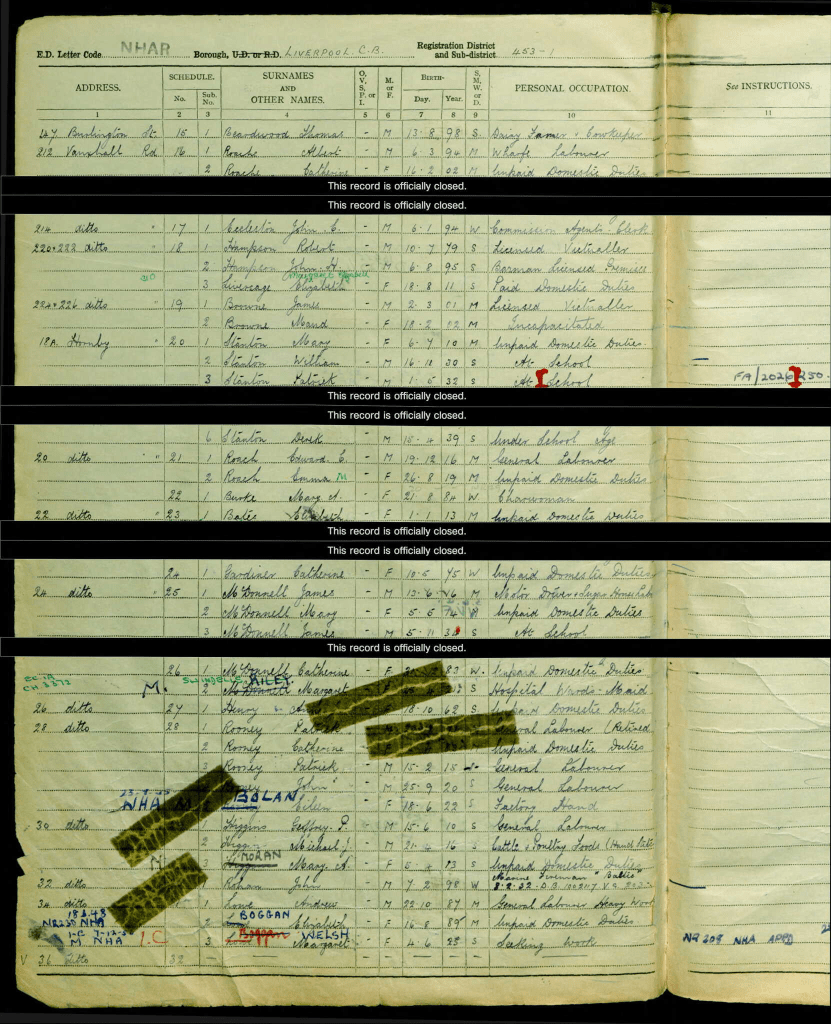

By the time of the 1939 England and Wales Register, Edward was recorded as a general labourer, one of the most common occupations in Liverpool at the time. The term covered a wide range of work — from construction to factory labour — but in Liverpool it often meant employment linked to the docks.

The city’s dock system employed tens of thousands of men. Work was heavy, unpredictable, and physically punishing. Labourers loaded and unloaded ships, shifted cargo, and maintained the endless infrastructure of warehouses, cranes, and quaysides that kept Britain’s trade flowing.

The Casual Labour System

Much of Liverpool’s dock work operated under a casual labour system. Men like Edward gathered each morning at hiring stands, or “pens,” waiting to be chosen by foremen for a half-day’s work. A man’s livelihood could depend on being selected from the crowd. The lucky ones worked long hours for modest pay; those left behind faced another day without wages.

It was a system that bred uncertainty but also deep camaraderie. Dockers relied on one another, shared information about available jobs, and built mutual aid networks to survive lean times. For men supporting large families, the stakes were high. The cost of the tram fare to the docks could be painful when work was scarce, so many stayed near the hiring stands all day, hoping for a second chance in the afternoon call-up.

Unions and Solidarity

By the early 20th century, Liverpool’s dockers had built one of Britain’s most active union traditions. The National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL) fought to protect its members from exploitation and to secure fairer hiring practices. Union membership was essential: employers often selected union men first, recognising the stability that organised labour could bring to an otherwise chaotic system.

For Edward, union membership would have been more than a formality. It meant solidarity, community, and a measure of security in an unpredictable world. The union also provided small financial supports during injury or unemployment — modest sums that often made the difference between survival and destitution for dock families.

The Realities of the Work

Dock labour was among the most dangerous jobs in Britain. Every shift carried the risk of injury or worse — falling cargo, collapsing loads, or accidents with cranes and machinery. Men frequently suffered crushed limbs, chronic back problems, or worse. Pay was handed out weekly, usually on Saturday afternoons, meaning a man might wait several days for his earnings after short stints of work.

Despite these hardships, dock work carried a sense of pride. The docks were Liverpool’s lifeblood, and every crate lifted or rope secured connected men like Edward to the city’s global trade. In that sense, he and his peers were custodians of Liverpool’s industrial power — anonymous but indispensable figures in Britain’s working landscape.

Family and Home Life

Edward and Emma had ten children, however, sadly one passed away when only a few weeks old. Their remaining nine children went on to build families of their own — a testament to their strength, love, and perseverance in a time when family life could easily be unsettled by economic hardship.

Their household would have been lively and likely noisy — a mix of laughter, hard work, and the constant balancing act of managing money, meals, and children in an era before social safety nets were strong.

Emma played a vital role in holding the family together. Like many dockers’ wives, she probably managed the household finances with ingenuity and care — stretching Edward’s wages, taking in extra work when needed, and maintaining a welcoming home that offered stability amid economic uncertainty. In Liverpool’s tight-knit communities, neighbours helped one another through illness, unemployment, or bereavement, and the Roach household would have been part of that wider web of mutual support.

Surviving on Uncertain Wages

Life for a dock labourer’s family was never easy. The irregularity of employment forced families to develop creative strategies for survival. “Subbing” — taking small cash advances from employers or local shopkeepers — allowed men to buy lunch or bus fare while waiting for payday. Many families also relied on pawnbrokers, temporarily trading household goods early in the week and redeeming them when wages came in on Saturday.

These were common, almost institutionalised forms of working-class credit. Though precarious, they allowed families to bridge the gaps between work and want. The Roaches’ ability to maintain a stable household, raise six children, and keep everyone clothed and fed demonstrates an extraordinary resilience shared by many Liverpool dock families of the time.

Later Years and Passing

By the 1970s and 1980s, Liverpool’s docks were in decline. Containerisation and industrial restructuring had eroded the traditional labour system. The working men who had powered the port for generations were gradually replaced by mechanised handling and reduced workforces.

Edward lived to witness this transformation — a lifetime’s industry disappearing before his eyes. Yet his own values of hard work and solidarity would have endured within his family, passed down to children and grandchildren who inherited the quiet pride of Liverpool’s working class.

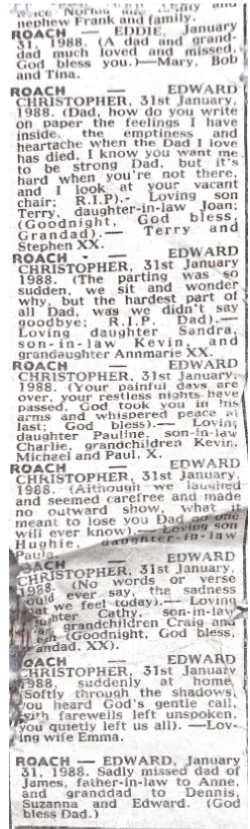

On 13 January 1988, Edward died suddenly at home, aged 71. Newspaper notices described his passing as “sudden,” suggesting a heart attack or similar event. The tributes that followed reveal a man deeply loved and widely respected. His wife Emma’s message — “Softly through the shadows, you heard God’s gentle call, with farewells left unspoken, you quietly left us all” — captured both the shock of his loss and the tenderness of a partnership that had lasted more than fifty years.

Multiple obituary notices were placed by his children and grandchildren, each expressing affection, gratitude, and the pain of separation. The repeated words “Dad” and “Grandad,” “much loved,” and “sadly missed” speak to the central place Edward held in the lives of those around him. These personal tributes, more than any document or record, offer a window into his character — a hardworking, kind, and steady man who was the emotional anchor of a large family.

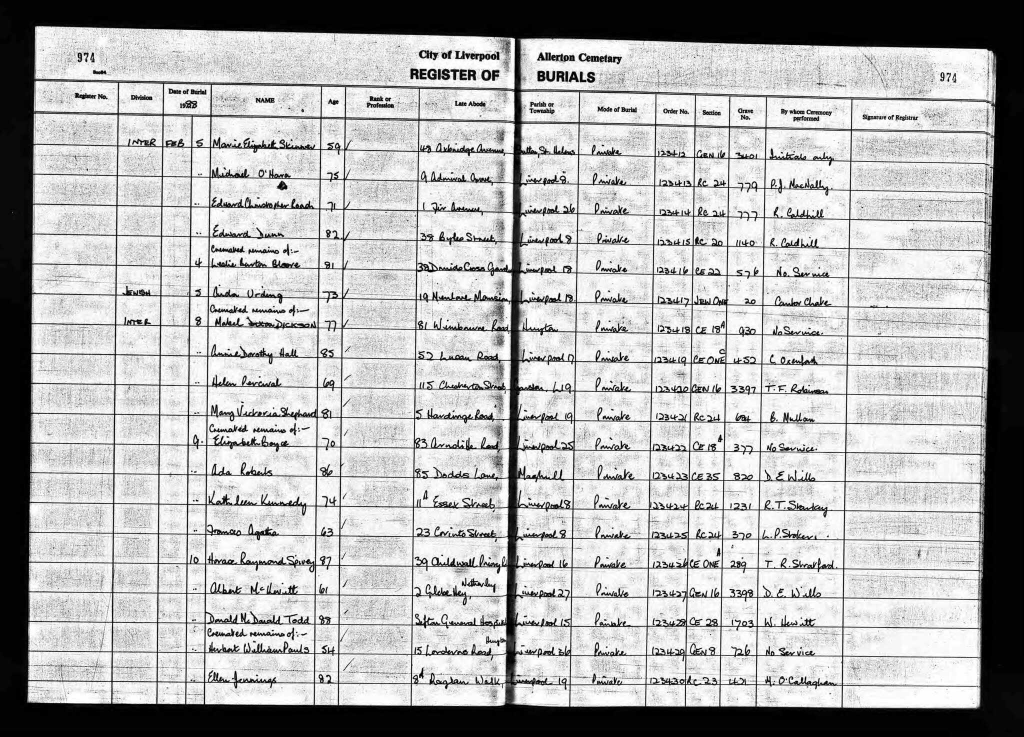

Burial and Resting Place

Edward was laid to rest at Allerton Cemetery in Liverpool, one of the city’s major municipal burial grounds established in the early 20th century. The cemetery holds thousands of Liverpool residents who contributed to the life and labour of the city, from dockers and seamen to civic leaders and artists.

His burial in the general section suggests a modest, dignified service — one fitting for a man who lived a life defined by quiet service to his family and community. The cemetery’s location in south Liverpool would have been accessible for relatives to visit, and it remains a peaceful resting place within the city he called home.

A Life in Context

Edward Christopher Roach’s story cannot be separated from the story of Liverpool itself. He was born when the city was at the height of its industrial power, lived through two world wars, and witnessed its economic transformation in the post-war decades. The arc of his life mirrors the wider journey of Britain’s working class through the 20th century — from hardship and insecurity toward gradual stability and social progress.

Liverpool’s dock system, where Edward likely spent much of his working life, was both the city’s pride and its burden. The casual labour system created deep economic insecurity but also forged some of the strongest communities in Britain. Neighbourhoods around the docks — Toxteth, Kirkdale, Bootle — became symbols of resilience, mutual support, and working-class solidarity. Men like Edward formed the backbone of these communities, their efforts largely unseen but indispensable to the life of the city.

The major dock strikes and union movements of the 20th century — from 1911 through to the post-war disputes — shaped the environment in which Edward worked. Each wave of collective action sought to improve the lot of men like him, ensuring better safety, fairer pay, and eventually the gradual end of casual hiring.

Legacy

By the time of his death, Edward had seen his six children grown and settled, and he had become grandfather to a new generation. One grandson was named Edward, continuing the family name and honouring the patriarch who had worked tirelessly to build their foundation.

His descendants’ lives — including that of my wife Sarah, his granddaughter — carry the quiet legacy of his endurance. The values that sustained him through a lifetime of labour and uncertainty remain part of his family’s character: a belief in hard work, loyalty, and the importance of family ties.

While his name may never appear in official histories of Liverpool’s docks, his story represents the thousands of working men whose labour sustained the city’s prosperity. The dignity with which he lived his life and the love he inspired in those around him are, in the truest sense, his enduring memorial.

Reflection: The Broader Story

Edward Christopher Roach’s life is a lens through which we can glimpse the lived reality of Britain’s industrial heartlands. His story combines the intimate — family, love, endurance — with the grand sweep of social history. Through him, we see the transformation of Liverpool from imperial port to post-industrial city, and the unbroken thread of working-class culture that carried through those changes.

In many ways, Edward’s life captures the essence of what this family history project seeks to preserve: not just names and dates, but the human stories behind them. His was a life of work without fame, service without recognition — yet through his labour, love, and legacy, he helped shape the lives of generations that followed.

Hi Ann-Marie, I’m genuinely sorry that this has upset you. The site is very much a work in progress and…

This is disgusting, as a part of this family it’s incredibly inaccurate. Very jaded and entirely inappropriate you have not…

Leave a comment