I think of Ernie as the kind of man who quietly holds a family together. He wasn’t interested in grand statements or polishing his own legend; he worked hard, kept his promises, loved his people, and let the rest take care of itself.

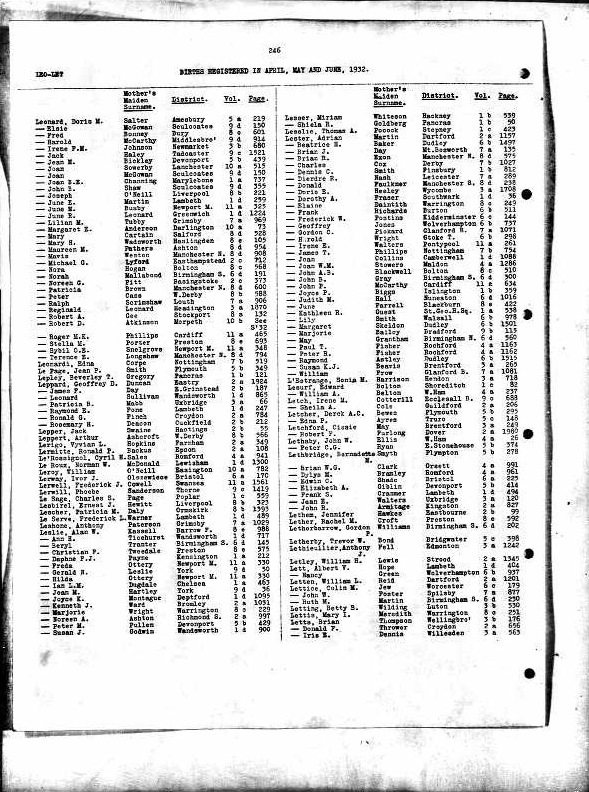

Born on 19 June 1932 in Toxteth and passing peacefully at home in Halewood on 2 March 2010, his seventy-seven years mapped neatly onto Liverpool’s changing fortunes—from the busy cargo sheds of his youth through containerisation, severance, and, finally, the steadier rhythms of retirement.

Roots: Toxteth, the Docks, and a Channel Islands Name

Ernie arrived in the world in Toxteth Park, South Liverpool, a dense patchwork of terraced streets, corner shops, and the kind of door-to-door familiarity that made neighbours into a second family. The Lesbirel name carries its own small story—its Channel Islands origins show up in older records—but by the 1930s the family was fully woven into Liverpool’s dockland culture. His father, also Ernest John, worked as a dock labourer, and the line from father to son was more than a job title. It was a language, a rhythm, an expectation that you’d do your shift, look out for your mates, and bring your wage packet home. That inheritance—practical, stoic, unshowy—set the tone for Ernie’s life.

He came of age at a time when the city was still configured around its port. The docks weren’t just an employer; they were the reason streets existed where they did, why shops sold certain goods, why pubs kept certain hours, and why family life bent itself around tides, sailings, and overtime. To grow up in Toxteth and step onto the docks as a young man was to join the civic bloodstream. That’s how I picture Ernie: moving from boyhood into the long stride of work with a kind of matter-of-fact pride that didn’t need saying out loud.

Work: From Call-On Casual to a Registered Stevedore

“Dock labourer” and, later, “stevedore” are more than labels on certificates. They describe a progression from general, often casual work—turning up at the stands and hoping your name would be called—to the more skilled, crew-based handling of cargo, with knowledge of loads, balance, and machinery. In Ernie’s early years, the docks lived by the call-on system, an unfair and precarious way to earn a living. You might work a long day in all weathers one week and be turned away the next. Wages wobbled. Tempers frayed. Families learned to stretch and scrimp.

The 1960s introduced something different. With the National Dock Labour Scheme, registration brought a measure of stability to men like Ernie: a regular wage, allocation to a stevedoring company, and the ability to plan. That shift mattered. It didn’t make the work less heavy or less risky, but it took the edge off the daily uncertainty and, in a very practical sense, made family life easier to manage. Ernie’s pride was not in resisting change for its own sake, but in adapting and keeping his end up—learning new kit, following safer procedures, and becoming the sort of man a gang trusted.

I imagine him on a cold morning, breath fogging the air, sleeves rolled, the choreography of hooks, slings, signals, and shouts all second nature. Docker, stevedore—both words capture the same essence: competence built by repetition, care for the lad working beside you, and the quiet knowledge that a lot of money and safety rides on doing it right.

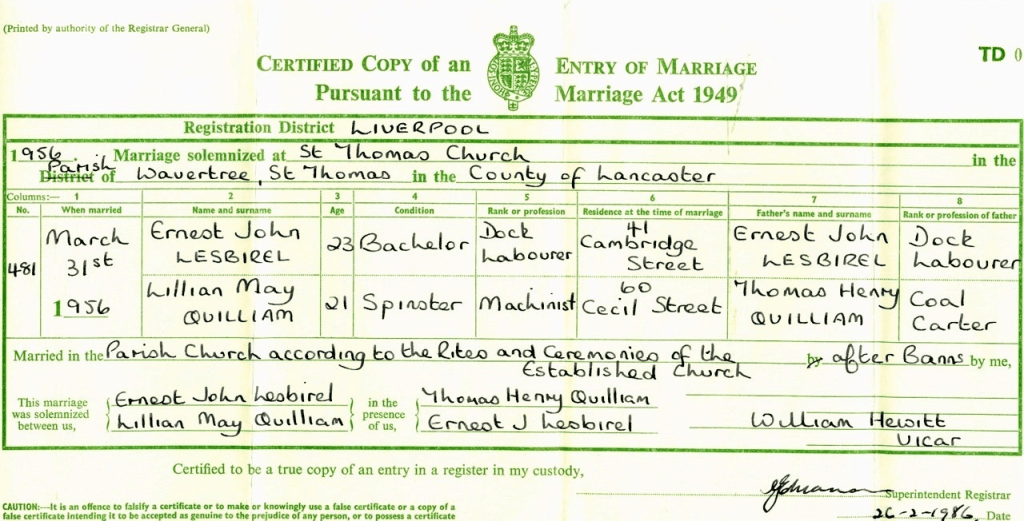

Marriage: Ernie and May

On 31 March 1956, twenty-three-year-old Ernie married Lillian May Quilliam—May to everyone who mattered. He was a dock labourer; she was a machinist. The pairing makes sense: two working people with practical skills, steady tempers, and a shared understanding that life is mostly made up of doing ordinary things well. They started out in south Liverpool, where families stacked neatly along the terraced streets—wash on the lines, kids on the pavements, Sunday dinner on the go.

Their son, arrived in 1957, and their daughter, followed in 1960. Those dates sit exactly where you’d expect in a story like this: kids born as the household steadied, then the long years when you’re paying bills, keeping shoes on growing feet, and trying to put something by. If ever a couple embodied that old-fashioned phrase “good providers,” it was Ernie and May—not flashy, not precious, but reliable in a way you could set your watch by.

Family Life: Love, Routines, and the City’s Pulse

The picture that comes through—stronger the closer we get to Ernie’s later years—is a home built on small, faithful rituals. He wasn’t a speechmaker. He was a doer. In that sense, the family’s happiest images of him are exactly the ones that ring truest: the Sunday paper tucked under his arm, the kettle on, the same easy chair, the same wry comment about the match or the neighbours, and the laughter that bubbles up when a grandchild comes through the door.

That’s not to romanticise things. Work was tough and the city sometimes tougher. The 1970s and early 1980s were heavy with industrial dispute and economic uncertainty. But the point about Ernie is that he handled what was in front of him. He went to work, did the job, came home, and kept faith with his people. If there is a particular dignity from that era, it lives right there.

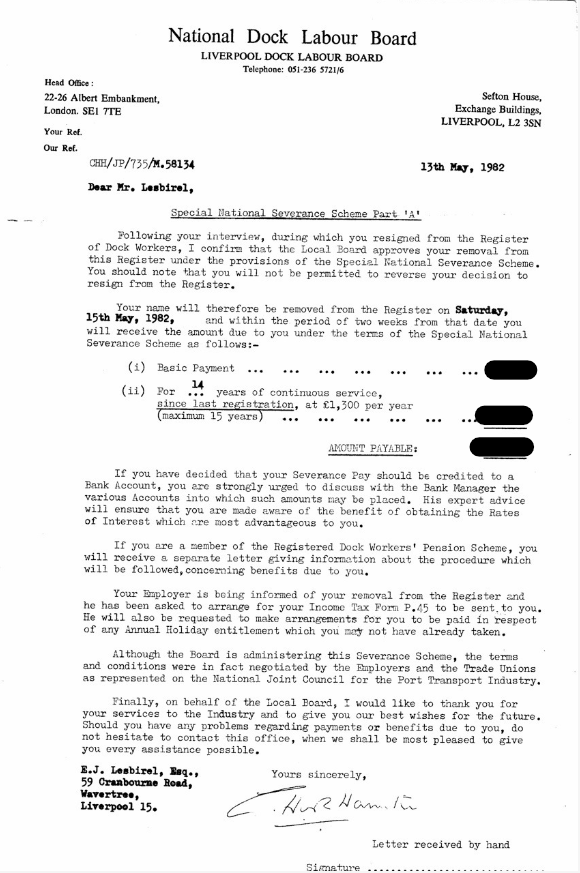

Leaving the Docks in 1982: What It Was—and What It Wasn’t

Ernie left the docks in 1982 under a severance scheme. Containerisation had changed the port beyond recognition, and many men of his generation took packages that reflected long service and an industry pivoting to new ways. Here’s the important nuance that sometimes gets flattened in retelling: leaving the register at forty-nine did not mean Ernie “retired” at forty-nine. It meant he left dock work at forty-nine.

That distinction matters. A man who has done hard, skilled labour for decades doesn’t stop being industrious when a letter arrives; he simply stops being a docker. The family timeline that follows bears that out. Ernie stayed active and purposeful, moved through the 1980s and into the 1990s with his usual steadiness, and reached retirement age in the ordinary course of things. If anything, the severance simply allowed him to reshape his working life and, eventually, to set up the kind of retirement he and May actually wanted.

The Move to Halewood—In the 1990s, and On Their Terms

Ernie and May moved from Wavertree to Halewood in the 1990s, by which time they were of retirement age, a step taken deliberately for their later years: quieter streets, a garden to fuss over, and—most importantly—proximity to family.

Curlew Grove gave them exactly that. Halewood sits close enough to Liverpool that the city remains in your voice and your bones, but daily life has a calmer cadence. For Ernie, the Sunday walk to fetch his paper, the short hop to his nearby family, and the dependable routine of the kettle and the chat became a kind of weekly liturgy. If you ask me to pick a single image that sums him up, it’s that one: Ernie at the door, “Alright, son?” on his lips, a folded broadsheet in his hand.

Liverpool FC: The Kop, the Boys’ Pen, and a Shared Language

Football wasn’t background noise in Ernie’s world; it was a language he spoke fluently. He stood on the Kop at Anfield, shoulder-to-shoulder with thousands of others, part of that living tide of song and banter. His son started in the Boys’ Pen—that rite of passage—before graduating to the Kop proper when he was old enough. There’s a whole father-and-son novel tucked into that one detail: the first time the lad steps out from the railings onto the big terrace, the way the sound hits you, the look you give each other when the ball ripples the net.

For men of Ernie’s generation, the club threaded through everything. The decades of dominance under Shankly, Paisley, and Fagan weren’t just trophies; they were a ballast in a city facing economic storms. The tragedies, too—Heysel and Hillsborough—were borne collectively, the way Liverpool bears and remembers. I don’t need to hear Ernie’s exact words to know the tone he would have used: plain, heartfelt, and honest. The club wasn’t a hobby; it was part of how he recognised himself and his place in the world.

The Children at the Centre

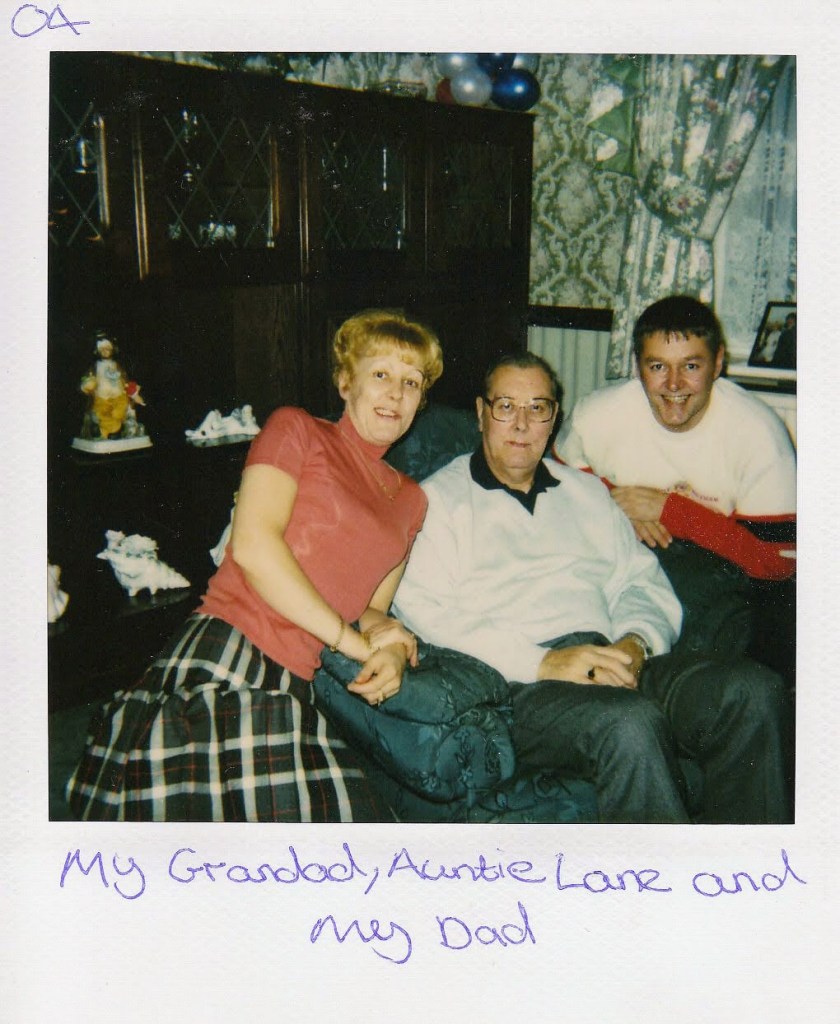

Ernie was never sentimental about his role, but he was deeply proud. His son, born in 1957, stayed close—geographically and emotionally. He’s the one who handled the formalities when Ernie died, the one who shared those Sunday cups of tea and match post-mortems, the son whose door Ernie could always knock. Lorraine, born in 1960 (died 2020), brought her own light into the room. And to be clear on the timeline that matters deeply to the family.

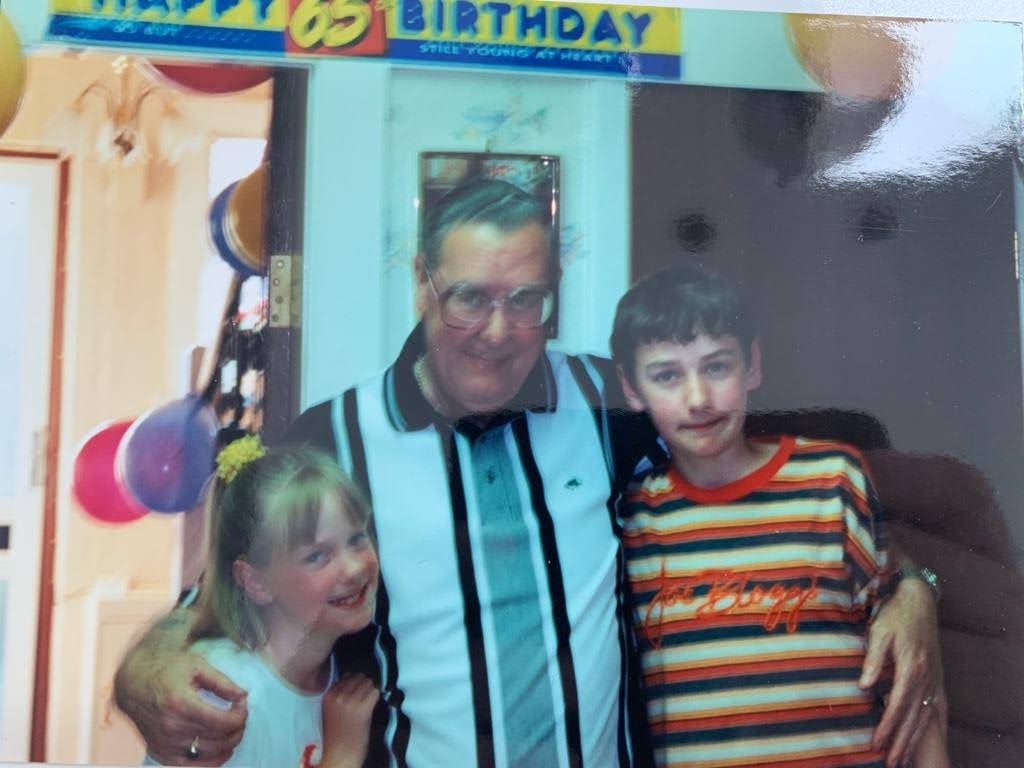

Between them came grandchildren, and with them a gentler chapter for Ernie: the steady presence, the funny aside, the pocket money slipped across with mock seriousness, the “don’t tell your nan” wink that fooled precisely no one. If the gravestone calls him “a much-loved husband, dad and grandad,” it’s because those roles were the point. The work was the means; the family was the end.

Health, Ageing, and the Final Winter

Ernie died peacefully at home in Halewood on 2 March 2010. The medical story is familiar—heart disease in the background, bronchopneumonia in the foreground—a combination that often turns a winter infection into a final decline. I’m struck by two things in that ending. First, the peacefulness of it: to slip away in your own bed, in your own house, with your own things around you, spares a family a particular kind of pain. Second, the prompt, capable way the family handled what followed speaks to how they’d always handled things—together, with care, and without fuss.

I don’t gild this part; it doesn’t need it. A life that started in a terraced house in Toxteth and passed through a half-century of hard, honest days came to rest in a modest, tidy home in Halewood. If that sounds simple, that’s because simplicity was the prize Ernie aimed for and won.

May: The Partner in Every Sense

It’s easy to centre Ernie in his own story—and right to do so—but May is everywhere in it. From machinist to cleaner (retired), from young bride to grandmother, she was the counterpoint and the companion. Two steady people found each other early and stayed the course. When I consider their move in the 1990s, I see her hand as much as his: choosing a place that made weekends easier, grandchild visits more frequent, and daily life a touch gentler. The inscription “much-loved husband, dad and grandad” contains, without needing to say it, “much-loved wife, mum and nan.” One role articulated the other.

Character: What People Remember

Strip away the dates and documents and what remains is character. People talk about Ernie as steady, modest, and dependable—the sort of man who reads the room, fixes the thing that’s broken, and never makes himself the story. They remember him listening more than he spoke, adding a line when it mattered, and letting silence carry the rest. For men who worked in hazardous environments, there’s a particular virtue that comes from doing your task carefully, keeping your word, and not making drama for other people to navigate. Ernie radiated that virtue.

I suspect he measured success the way older Liverpudlians tend to: were the kids alright? Was the rent or mortgage paid? Was there food in the house? Could he look May in the eye and say today was an honest day? All the other markers—titles, applause, “being known”—weren’t his currency.

Correcting the Record: Four Key Clarifications

Because family history sits at the junction of memory and paperwork, I want to mark the four factual points that needed tidying:

- 1982 was when Ernie left the docks, not when he “retired.” He departed under a severance scheme at forty-nine and moved forward with life; retirement came later, in the ordinary way.

- The move to Halewood belongs in the 1990s, when Ernie and May were of retirement age—a deliberate choice for their later years, not an early-life relocation.

- Liverpool FC details matter: Ernie stood on the Kop, and his son began in the Boys’ Pen before stepping into the Kop proper. That father–son trajectory is part of how their bond expressed itself.

- Lorraine’s passing came in 2020, ten years after Ernie—so she did not predecease her dad. The family’s grief has its own timeline, and the words should honour that.

Getting these right isn’t pedantry; it’s respect. When a life is told by people who loved the man who lived it, accuracy becomes a form of care.

Legacy: Ordinary Greatness

What, then, is the legacy of Ernest John “Ernie” Lesbirel? I’d call it a textbook case of ordinary greatness: the quiet living of a good life. He carried the dockland ethic into the way he fathered, the way he showed up for May, and the way he grandparented. He adapted to a changing industry without bitterness, made a later-life home that served his family, and kept his sabbath of small pleasures intact—paper, kettle, chat, football.

There’s a temptation in family writing to turn the everyday into the epic. I don’t think Ernie needs that. The scale of his life doesn’t come from heroics; it comes from repetition—the same good choices made for decades. He treated people well, looked after his own, and kept faith with a city that asked a lot and gave a lot back. That’s Liverpool in a nutshell, and it’s Ernie all over.

Closing: Why We Tell It This Way

I’ve kept this account formal enough to stand as a record and friendly enough to sound like me, because that’s how I think a good family story should read—solid in its facts, warm in its tone, and careful with its language. If you remember only one line, let it be the one on his stone: “a much-loved husband, dad and grandad.” It’s simultaneously an inscription and a thesis. Ernie built a life that earned those words, and the city he loved is threaded through every letter.

He was a Liverpool docker, a Kopite, a husband to May, a dad, and a grandad with a pocketful of small kindnesses. He left the docks in 1982 but didn’t stop being useful; he moved to Halewood in the 1990s because it made family closer; he kept the Sabbath of ordinary Sundays. When I set his dates—1932 to 2010—between those details, I see a life that adds up cleanly. That’s how I want him remembered: not for what was flashy, but for what was faithful.

Hi Ann-Marie, I’m genuinely sorry that this has upset you. The site is very much a work in progress and…

This is disgusting, as a part of this family it’s incredibly inaccurate. Very jaded and entirely inappropriate you have not…

Leave a comment