This comprehensive report examines the remarkable life of Frederick Edward Rose through his own autobiographical memoir and extensive historical research, revealing the extraordinary journey of a Victorian working man who served his country with distinction across three continents and four decades of military service.

Early Life and Background

Frederick Edward Rose was born in Bristol on 14 March 1840, during the early years of Queen Victoria’s reign.

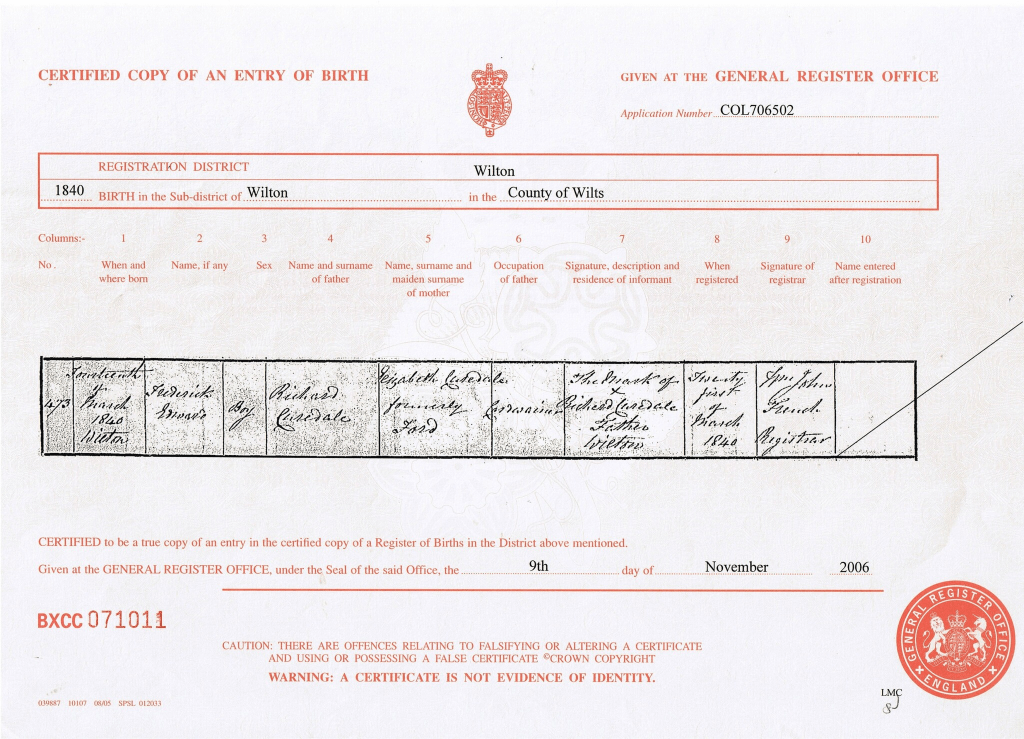

The Curedale Name Mystery: A Victorian Family Transformation

Genealogical research has uncovered compelling evidence that Frederick Edward Rose was actually born Frederick Edward Curedale on 14 March 1840 in Wilton, Wiltshire, to Richard Curedale, a cordwainer (skilled shoemaker), and Elizabeth. This discovery emerged through meticulous detective work examining birth certificates, census records, and family documentation that reveals a fascinating case of Victorian-era surname adoption. The birth certificate for Frederick Edward Curedale matches perfectly with Frederick’s autobiographical details regarding his birth date and circumstances, while subsequent family records demonstrate a gradual transition from “Curedale” to “Rose” during the 1840s.

The transformation appears to have occurred systematically within the family: Richard James was born “Richard James Rose Curedale” in 1838, Frederick as “Frederick Edward Curedale” in 1840, and Sarah Matilda as “Sarah Matilda Rose” in 1845, showing the parents listed as “Richard Curedale Rose and Elizabeth.” By the 1841 census, the entire family was recorded as “Rose” in Wilton, and this identity remained consistent through their relocation to Gillingham and Frederick’s subsequent military career. Such surname changes were legally permissible under English common law without formal documentation, provided no fraudulent intent existed, and were not uncommon among skilled working-class families seeking social advancement during the Victorian era. The adoption of the more familiar “Rose” surname may have been motivated by business considerations for Richard’s cordwainer trade, social mobility aspirations, or simply preference for a more conventional English name as the family relocated and established themselves in new communities.His father was described as a Londoner while his mother was a native of Bristol, representing the mobile population characteristic of early Victorian England. When Frederick was quite young, his family relocated to Gillingham, a small market town in Dorsetshire near the borders of Wiltshire and Somerset, positioned four miles northwest of Shaftesbury. This rural market town would prove formative in his early development.

In Gillingham, Frederick attended the village school, which he described as “a very good country school, and quite free to day scholars”. This educational opportunity was significant for a working-class child in the 1840s and 1850s. The Gillingham Free School, established in 1516, had a distinguished history of educating local children and would later become the Grammar School. Frederick’s education there would have provided him with basic literacy and numeracy skills that would serve him well throughout his military career. After several years in Gillingham, the Rose family returned to Bristol, where Frederick spent his youth “much as the lives of other lads of the same age”. By trade, Frederick learned carpentry, a skilled profession that was recorded on his military attestation papers at age 18.

Military Enlistment and Early Service

Frederick’s military career began through a chance encounter that would define the next two decades of his life. On 1 August 1858, while visiting his married sister in Slough near Windsor, he attended a Royal review of troops at Aldershot. This spectacular military display made a profound impression on the 18-year-old carpenter. The following morning, as he prepared to leave, Frederick encountered the Northumberland Fusiliers marching to the station and learned from an old soldier that the regiment was about to embark for foreign service.

The veteran soldier, disappointed that his poor health prevented him from accompanying the regiment overseas, invited Frederick to visit the barracks. What began as casual curiosity transformed into a life-changing decision when Frederick enlisted in the 2nd Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers that same day. His Certificate of Attestation recorded him as Frederick E. Rose, age 18, height 5 feet 7 inches, with a fair complexion, light blue eyes, and his trade listed as carpenter.

The Northumberland Fusiliers, originally raised in 1674, had become the 5th Regiment of Foot in 1751 and gained the territorial title ‘Northumberland’ in 1782. In 1836, the regiment was designated as fusiliers, becoming the 5th (Northumberland Fusiliers) Regiment of Foot. This distinguished regiment had served with honor across the globe and would provide Frederick with opportunities for advancement and international service that few working-class men of his era could imagine.

Training and Deployment to Mauritius

Frederick’s initial military training took place at Aldershot, where he was briefly assigned to clerical duties in the orderly room before requesting transfer to work as a military hospital orderly. On 17 August, the depot relocated to Pembroke Docks, a fortified military installation in Wales characterized by wooden huts surrounded by a strong stone wall. The camp housed six depot battalions, each commanded by captains under the overall authority of a Lieutenant Colonel.

At Pembroke Docks, Frederick underwent three months of recruit drill training and three weeks of musketry instruction, transforming from civilian carpenter to trained soldier. The military infrastructure at Pembroke Docks was substantial, with facilities for accommodation, training, and garrison duties including guarding the important naval dockyards where warships were under construction.

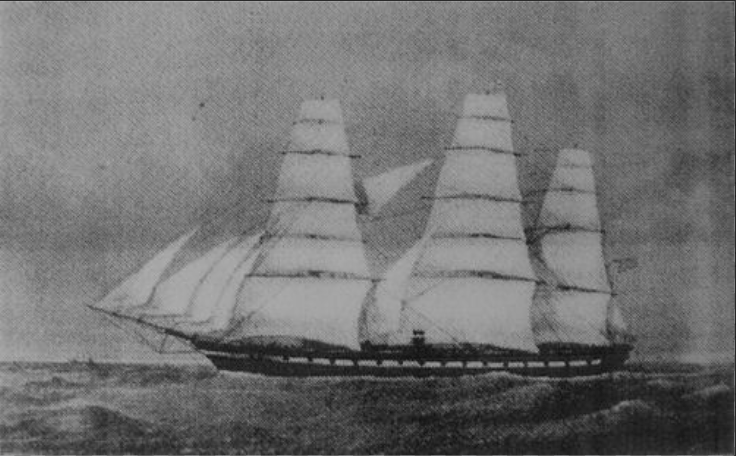

On 1 March 1860, Frederick departed Pembroke Docks with a draft of soldiers bound for overseas service. After a brief stop in Cork, they embarked at Queenstown on 10 March aboard the hired troopship ‘Donald Mackay,’ a first-class clipper sailing ship belonging to the Black Bull Line of Liverpool. The vessel carried approximately 1,200 troops alongside the 2nd Battalion 24th Regiment, all bound for Mauritius.

The voyage to Mauritius proved both arduous and memorable. Frederick experienced the harsh realities of troopship travel, including overcrowding, limited fresh water, and basic rations of biscuits, salt pork or beef, chocolate, and tea, supplemented by daily rum rations and lime juice in tropical waters. The journey was marked by dramatic incidents including a severe storm in the Bay of Biscay where Frederick, exhausted from working the pumps, fell asleep on deck and awoke “like a half drowned rat” on his 20th birthday. Tragically, a young seaman was killed during the storm, and his body was committed to the sea.

Service in Mauritius (1860-1863)

The troopship reached Mauritius on 22 May 1860 after over two months at sea. Port Louis, the colonial capital, provided Frederick with his first experience of tropical military service. The British garrison occupied substantial stone barracks with broad verandahs, designed to accommodate companies of 100 men each. The tropical climate necessitated significant adaptations, including white duck clothing instead of European uniforms, and the use of coconut oil for lighting rather than candles.

Frederick quickly adapted to colonial military life and was promoted to Lance Corporal within a month of arrival. However, his advancement came with challenging responsibilities. He was appointed assistant warder at the military prison located within the barracks, a position that provided extra duty pay of one shilling per day. The role involved unlocking cells at 6 AM, supervising prisoner exercise, and maintaining detailed records including weekly weight measurements for the medical officer. Frederick found the prison duties distasteful and requested relief after only one day, despite the good pay and status associated with the position.

The regiment’s duties in Mauritius included both routine garrison work and responding to natural disasters. In June 1861, Frederick marched with the regiment to Mahebourg, a town 32 miles from Port Louis on the opposite end of the island. During their station there, a devastating cholera outbreak struck the island, affecting both military personnel and the civilian population. The epidemic tested the regiment’s medical preparedness and discipline. Thanks to the vigilance of their medical officers, who maintained constant watch and kept bottles of astringent medicine in every barrack room, the regiment’s death toll remained relatively low compared to other units.

During the cholera outbreak, Frederick was assigned to command a small party on Isle de Passe, a small island four miles from the mainland. When a hurricane struck while they were stationed there, no boats could reach them with supplies, forcing the detachment to survive on very short rations until the storm subsided. This experience demonstrated Frederick’s growing leadership capabilities and his ability to maintain discipline under extreme conditions.

Transfer to South Africa (1863-1867)

On 20 July 1862, Frederick’s regiment returned to Port Louis, and on 16 April 1863, they embarked on the government steamship ‘Himalaya’ for South Africa. The regiment was split, with the right half-battalion landing at Durban for service in Natal Colony, while Frederick’s left half-battalion proceeded to British Kaffraria (now Eastern Cape Province) and landed at East London on 27 April 1863.

East London presented a harsh frontier environment. Located at the mouth of the Buffalo River, the port could only accommodate surf boats due to constantly rough conditions. The troops were housed under canvas between Fort Glamorgan and the river banks, with a nearby Kaffir village of approximately 20,000 inhabitants. The region was frequently battered by sandstorms of such intensity “that it is scarcely possible to breath while they last, and the huts are blown down all over the camp”.

Frederick’s carpentry skills proved valuable in the frontier environment. On 10 January 1864, he was sent to King William’s Town with three other carpenters and attached to the Royal Engineers to construct new barracks. This assignment demonstrated his technical competence and trustworthiness, as skilled tradesmen were essential for military construction projects. The work involved building substantial fortifications and accommodation facilities in a challenging frontier environment.

The South African frontier was characterized by ongoing tensions with indigenous populations and constant military vigilance. In March 1865, Frederick joined a detachment of three companies at Kies-Kamma-Hoek, 28 miles further into the interior. This remote outpost was “almost surrounded by the Amatola mountains which are inhabited by a great number of warlike Kaffirs”. Intelligence reports indicated potential trouble, though no major incidents occurred during Frederick’s deployment there.

The military infrastructure in South Africa reflected the challenging frontier conditions. Frederick described encounters with the Cape Mounted Rifles, a corps “composed chiefly of Hottentots, with English officers and non-commissioned officers”. These indigenous troops were described as “small men, but good soldiers, and splendid horsemen” who provided essential communication services between military stations in the absence of railways.

In October 1865, Frederick’s detachment rejoined the main body of the regiment and marched to Grahamstown, arriving on 19 October. Grahamstown, located in Cape Colony about 600 miles from Cape Town and 96 miles inland from Port Elizabeth, resembled “a nice little country English town”. The settlement featured substantial shops, business houses, and a large open market place where weekly auctions were held for wool, ivory, ostrich feathers, and colonial produce. The presence of Sir Walter Currie’s estate, well-stocked with ostriches and zebras and open to garrison troops, provided welcome recreation opportunities.

Advanced Military Service and Return to England

Frederick’s frontier service included a posting to Fort Brown, an isolated station on the banks of the Great Fish River, where he served as second-in-command of a small detachment from 4 June to 18 August 1866. This remote location featured the only bridge in that part of the country, making it strategically important for military communications and civilian transport. The challenging environment required soldiers to be largely self-sufficient, making their own bread, crushing coffee berries, and hunting rabbits and buck for meat.

The natural environment around Fort Brown provided Frederick with memorable encounters with African wildlife. He described a colony of baboons dwelling in the high cliffs along the road from Grahamstown, noting their daily exercises and their apparent fear of soldiers. These observations revealed Frederick’s keen interest in his surroundings and his ability to find interest in the natural world despite the hardships of frontier service.

Following his return to regimental headquarters, Frederick was employed with another sergeant and sixty men to assist the Royal Engineers in constructing a reservoir. This major engineering project involved excavating, puddling, and blasting in the blazing African sun, but the men were “pleased to get the job” due to the extra pay involved. Frederick served as timekeeper and accountant for the project, demonstrating his administrative capabilities and mathematical skills acquired through his childhood education.

In April 1867, the regiment prepared to leave Africa. Frederick marched with the unit from Grahamstown to East London, a journey requiring careful logistical planning due to limited transport and the need to locate water sources for each night’s encampment. The march provided insights into colonial life, including interactions with indigenous peoples who would “sell almost anything for a ‘tickey’ (threepenny bit)”. Frederick’s observations of local customs, including noting that many indigenous people “go absolutely nude” in their villages, reflected the cultural contrasts experienced by Victorian soldiers in colonial settings.

On 10 May 1867, Frederick embarked for England aboard the troopship ‘Golden Fleece,’ an auxiliary screw steamship capable of 10 knots. The return voyage included stops at Simons Bay, Table Bay, and St. Helena, where they embarked a company of their regiment that had been stationed on the island. The ship reached Queenstown, Cork on 5 July, where it was coaled before proceeding to Dover, arriving on 9 July.

Professional Development and Marriage

Back in England, Frederick continued his military education and career advancement. He was posted to Dover, where the regiment occupied barracks at the Citadel and Western Heights. On 1 October, he attended the School of Musketry at Hythe, completing a prestigious course on 12 December when he was awarded a first-class certificate as a qualified Instructor in Musketry. This achievement represented significant professional advancement, as musketry instructors were elite soldiers responsible for training others in marksmanship and weapon handling.

In January 1868, Frederick undertook a course in gunnery at Castle Hill Fort, further expanding his military expertise. On 19 June, the regiment moved to Aldershot and went into camp at Rushmore Bottom. From 11-25 July, Frederick attended the National Rifle Association meeting at Wimbledon, participating in competitive shooting events that were the premier marksmanship competitions of the British military.

On 3 August 1868, Frederick made a crucial career decision, re-engaging to complete 21 years of service and earning two months’ furlough. This commitment reflected his satisfaction with military life and his desire to earn a full army pension. His professional competence was further recognized through various specialized assignments, including escorting prisoners and invalids, and participating in military exercises such as bivouacking in Woolmer Forest.

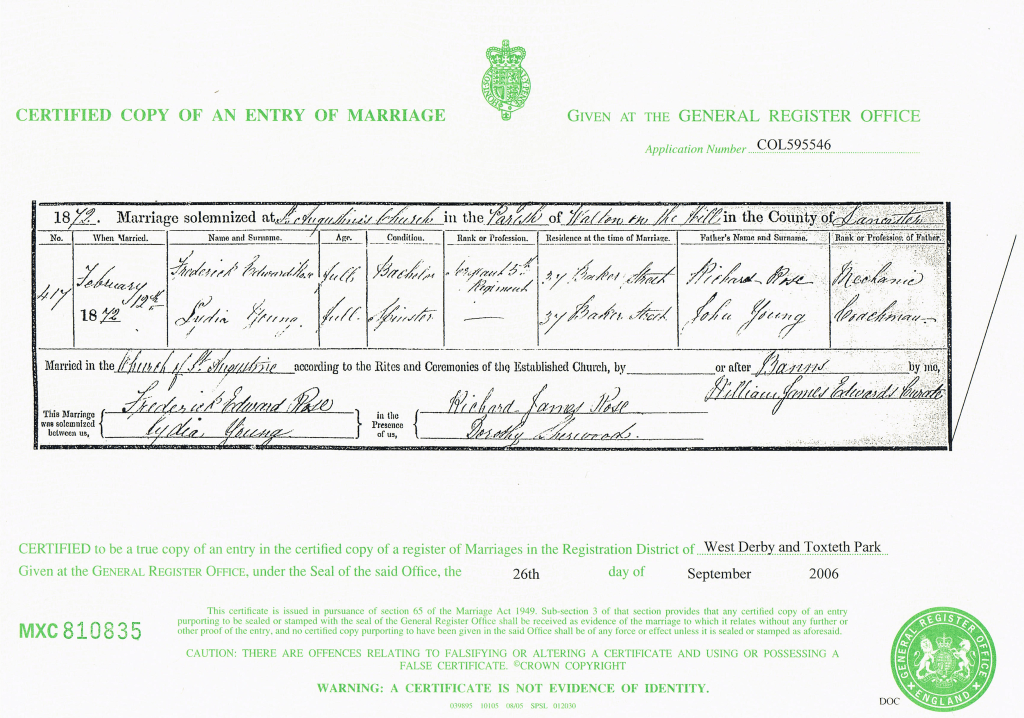

Frederick’s personal life took a significant turn during this period. On 12 February 1872, he was married to Lydia Young at St. Augustine’s Church in Liverpool and went to Manchester.

On 28 February, he returned to Dublin with Lydia, marking the beginning of his married life within the military community. His first child, Frederick Arthur, was born on 28 January 1873 in the barracks at Waterford.

Specialized Military Appointments

Frederick’s expertise and reliability earned him several specialized appointments during his service in Ireland. On 1 March 1872, he was appointed manager of the garrison canteen at Waterford, a position that required business acumen, integrity, and leadership skills. This role involved overseeing the supply of goods and services to soldiers, managing finances, and maintaining detailed records. In September, he was transferred to Clonmel, where he again served as manager of the garrison canteen.

During his Irish service, Frederick experienced significant historical events. In July 1871, he was in command of the Guard at Dublin Palace when the Prince of Wales and his two brothers, Prince Alfred and Prince Arthur, visited Ireland. A massive political demonstration in Phoenix Park, “numbering many thousands of Irishmen and women,” demanded an amnesty for political prisoners. When their request was refused, violent riots erupted lasting many hours, resulting in “about sixty killed, and hundreds injured”. Frederick’s guard faced constant danger from stones and missiles thrown over the palace walls by rioters who prowled the park throughout the night.

This experience placed Frederick at the center of significant political events during a turbulent period in Irish history. His position required maintaining military discipline while protecting royal visitors during civil unrest, demonstrating his capabilities under extreme pressure. The incident illustrated the complex political environment in which Victorian soldiers served, often finding themselves at the intersection of military duty and civilian political conflicts.

Transition to Militia Service

In April 1874, Frederick’s regular army service with the Northumberland Fusiliers concluded, but his military career continued in a new capacity. He was posted to Alnwick as a permanent staff member of the militia battalion of the Northumberland Fusiliers, holding the rank of Colour Sergeant Instructor. This position involved drilling and training recruits for the regiment, which annually embodied in July for four weeks of training and encamped near Alnwick Castle.

The Duke of Northumberland served as Colonel Commanding, with Major Grey as second-in-command, reflecting the high social status associated with militia leadership. Frederick’s role was crucial in preparing part-time soldiers for potential military service, ensuring they possessed basic military skills despite their civilian occupations. In December 1874, Colonel Grey died suddenly while visiting his seriously ill father, Earl Grey. The funeral, attended by the Prince of Wales, required Frederick to serve in the Guard of Honour. Standing close to the Prince during the cold, snowy ceremony, Frederick observed that “he felt the cold very much, and everybody was glad when the service was ended”.

During his Alnwick service, Frederick’s family continued to grow. His daughter Edith was born on 23 August 1874, followed by Lily on 16 June 1876, and Herbert Edward on 24 August 1877. The birth of Herbert Edward was particularly significant as he would become “Grandad Rose” in family memory. On 10 July 1877, Frederick was presented with a medal for long service and good conduct by Colonel Lord Percy, recognizing his exemplary military career.

Volunteer Force Career in Southport

On 1 January 1878, Frederick began a new chapter in his military career, moving to Southport and obtaining the position of Instructor to the 13th Lancashire Rifle Volunteer Corps. This appointment represented the culmination of his military expertise, as volunteer instructors were typically experienced regular soldiers who could train part-time civilian volunteers. The Volunteer Force, established in 1859 in response to invasion fears, had become an important component of British defense.

Frederick’s technical expertise was further enhanced when, on 2 February, he attended a course at the Royal Small Arm Factory in Birmingham, obtaining certification as a qualified armourer. This additional skill made him invaluable to volunteer units, as he could maintain and repair weapons as well as train personnel in their use. His combined qualifications in musketry instruction, drill, and armaments made him one of the most comprehensively trained military instructors in the volunteer system.

The 13th Lancashire Rifle Volunteer Corps regularly participated in annual training camps, providing Frederick with opportunities to maintain his military skills and train volunteer soldiers. His service record documents camps at Douglas, Isle of Man (1879, 1880, 1886, 1893); Colwyn Bay (1881); Chester (1883, 1888); and Ripon (1887, 1890, 1895). These camps brought together volunteer units from across Lancashire and provided intensive military training in realistic field conditions.

Frederick’s expertise was formally recognized in March 1889 when he was awarded a Certificate of the St. John Ambulance Society. This qualification in first aid and medical care complemented his military training and enhanced his value as an instructor. More significantly, he was presented by Colonel W. Maefie C.B. with “a handsome Purse containing £40, contributed by the Officers of the battalion as an acknowledgment of their appreciation” of his services. This substantial sum, equivalent to several months’ wages, demonstrated the high regard in which he was held by his military colleagues.

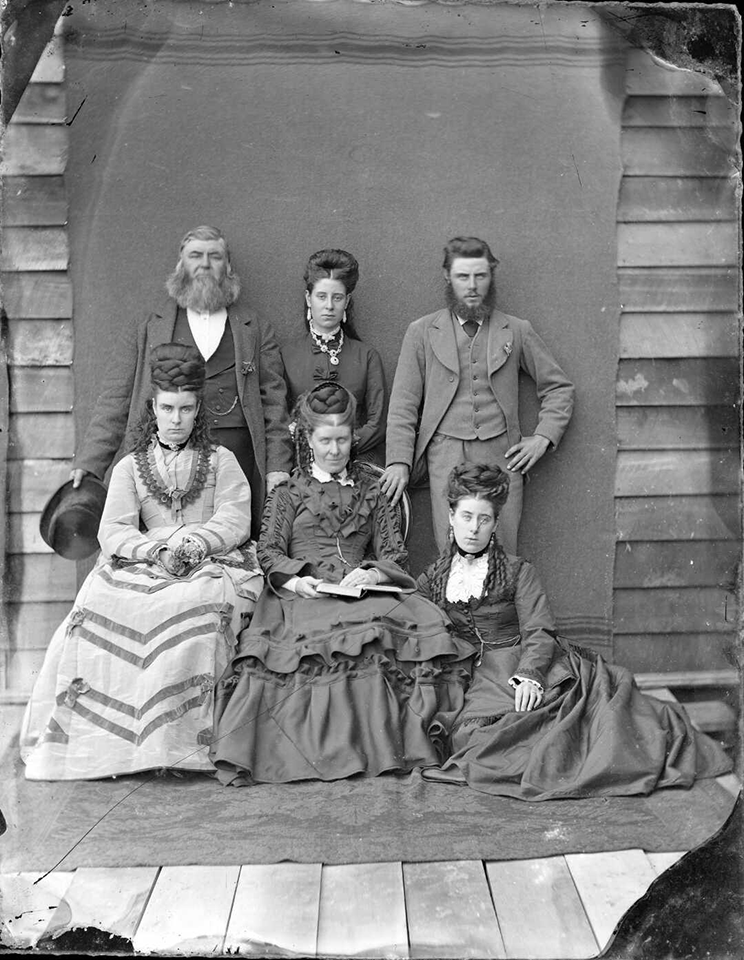

Family Life and Personal Achievements

Frederick’s personal life during his Southport years was marked by both joy and tragedy. His wife bore seven children between 1879 and 1889: Alfred Douglas (7 July 1879), Ernest Albert (25 September 1880), May (2 May 1882), Frank Bertie (3 July 1884), Ethel (15 March 1886), Hetty (26 July 1887), and Violet Hilda (3 July 1889). However, three children died in infancy: Alfred Douglas (13 February 1880), Ernest Albert (29 October 1881), and Ethel (3 September 1886). These losses reflected the high infant mortality rates of the Victorian era, even among relatively prosperous families.

As his children reached adulthood, Frederick witnessed their marriages and achievements. Frederick Arthur married Frances A. Whalley at St. Philip’s Church on 31 July 1902, followed by Edith’s marriage to Arthur Pederson at the same church on 3 September 1902. Herbert Edward married Florrie Wright at Seacombe Church, Cheshire on 23 June 1903, and Hetty married Harold Sampson at Bangor, North Wales on 15 October 1910.

The family experienced both joy and separation as some members emigrated. In November 1910, Arthur and his family sailed from Liverpool on the S.S. Friesland of the American Line, arriving in Philadelphia on 21 November. This emigration reflected the global mobility of working-class British families in the early 20th century, seeking economic opportunities in the expanding American economy. In January 1916, G. Wylie and Violet were married at St. John’s Church, Birkdale.

Recognition and Retirement

Frederick’s twenty years of service with the 13th Lancashire Rifle Volunteer Corps concluded on 9 September 1897. His contributions were formally recognized in Regimental Orders published by Colonel W. Maefie C.B., Commanding 3rd Volunteer Battalion, The King’s Liverpool Regiment: “The Commanding Officer desires to express his acknowledgment of the valuable services rendered to the Corps by Sergt Major Rose during his twenty years of faithful service… and takes this opportunity of wishing him in the name of the Corps every success in the future”.

Remarkably, Frederick was permitted to retain his rank and wear the uniform of the Corps on retirement, an honor that reflected his exceptional service. The Colonel Commanding appointed him secretary and accountant to the battalion, providing continued employment and recognition of his administrative capabilities. Upon retirement, the non-commissioned officers of the regiment presented Frederick with “a handsome gold watch, suitably inscribed,” demonstrating the personal affection and professional respect of his military colleagues.

Even in retirement, Frederick continued his connection to military service. On 10 July 1897, he attended a Brigade Camp at Llanberis with his former corps. Between 1902 and 1907, he participated in additional camps with various Imperial Yeomanry units, including the Duke of Lancaster’s Imperial Yeomanry, Lancashire Hussars Imperial Yeomanry, Earl of Chester’s Imperial Yeomanry, and Queen’s Own Royal Staffordshire Imperial Yeomanry. These continued engagements demonstrated his enduring commitment to military training and his valued expertise within the volunteer community.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Frederick Edward Rose’s life exemplifies the extraordinary opportunities and experiences available to working-class men through military service in the Victorian era. Born into modest circumstances in Bristol, he transformed himself through military discipline, education, and professional development into a respected leader and technical expert. His service spanned critical periods of British military history, including colonial expansion in Mauritius and South Africa, domestic security challenges in Ireland, and the development of the volunteer movement that would prove crucial in subsequent conflicts.

His detailed memoir provides invaluable insights into the daily experiences of Victorian soldiers, from the harsh realities of troopship voyages to the challenges of frontier warfare and the development of citizen-soldier traditions. Frederick’s career advancement from carpenter to sergeant major and certified instructor demonstrates the meritocratic opportunities within the Victorian military system for those willing to commit to long-term service and continuous learning.

The geographical scope of Frederick’s service—from the tropical conditions of Mauritius to the harsh frontiers of South Africa, the political tensions of Ireland, and the volunteer training camps of Victorian England—illustrates the global reach of the British Empire and the diverse experiences of its military personnel. His technical expertise in multiple areas, including carpentry, musketry, gunnery, and armaments, reflects the increasing specialization required by modern military organizations.

Frederick’s family life, documented in his memoir through births, deaths, marriages, and emigration, provides insights into the social mobility and global connections available to successful military families. His children’s various destinations and occupations demonstrate how military service could provide the foundation for broader social and economic advancement in the expanding opportunities of the early twentieth century.

The preservation of Frederick Edward Rose’s memoir and its detailed chronology of events provides historians with exceptional documentation of an ordinary soldier’s extraordinary life. His service record, spanning from 1858 to 1897 across multiple continents and military organizations, offers unique perspectives on imperial military service, colonial society, domestic security, and volunteer military traditions that would prove essential in Britain’s subsequent military challenges.

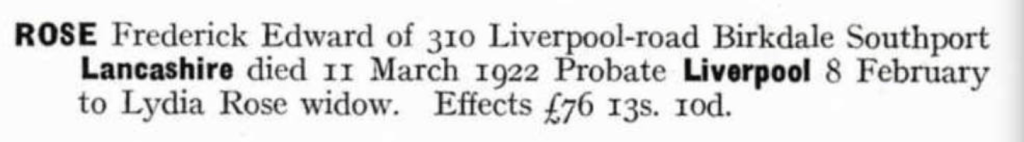

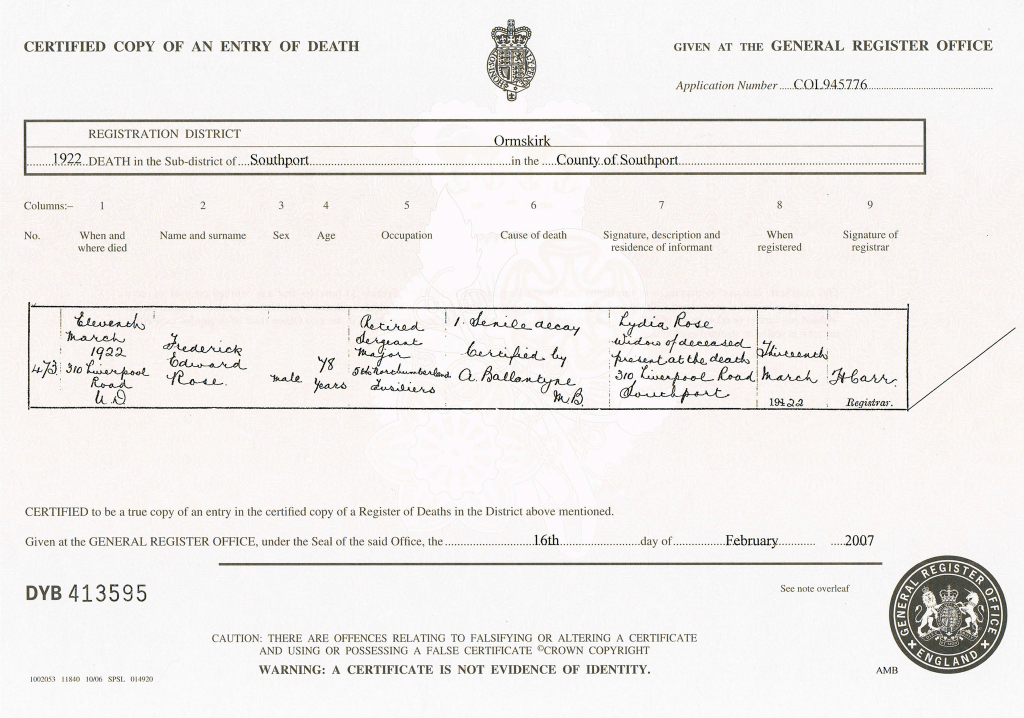

Frederick Edward Rose died on 11 March 1922 in Ormskirk, Lancashire, just three days before what would have been his 82nd birthday.

His life spanned the Victorian and Edwardian eras, witnessing the transformation of Britain from a primarily European power to a global empire, and the evolution of its military from a small professional force to a system incorporating millions of trained civilians. His memoir stands as a testament to the experiences of countless working men whose military service contributed to the expansion and defense of the British Empire while providing them with opportunities for personal advancement and global experience unimaginable in civilian life.

The comprehensive documentation of Frederick’s service, preserved in his own words, provides an unparalleled window into the lived experience of Victorian military service. From his chance enlistment at Aldershot to his honored retirement in Southport, his story illuminates the human dimension of British imperial history and the remarkable journeys possible for those willing to commit to military service during the great age of British global expansion.

Frederick Edward Rose’s Memoir

Hi Ann-Marie, I’m genuinely sorry that this has upset you. The site is very much a work in progress and…

This is disgusting, as a part of this family it’s incredibly inaccurate. Very jaded and entirely inappropriate you have not…

Leave a comment