Before delving into the details of Gladys Rosa Lillian Howey’s remarkable life, it’s important to recognise that her story mirrors the broader experience of countless working-class women in early twentieth-century Britain — women who bridged the gap between the old rural world of agricultural labour and the modern industrial life of the city.

Born into the reclaimed farmlands of Lincolnshire’s Fens and dying 74 years later in Liverpool, Gladys’s life spanned two world wars, economic depression, and immense social transformation. Her long relationship with John Joseph Howey — which lasted over three decades before they were finally able to marry — reflects the everyday complexities of working-class life, where love and partnership often preceded, or even replaced, legal ceremony.

Early Life in the Lincolnshire Fens (1905–1924)

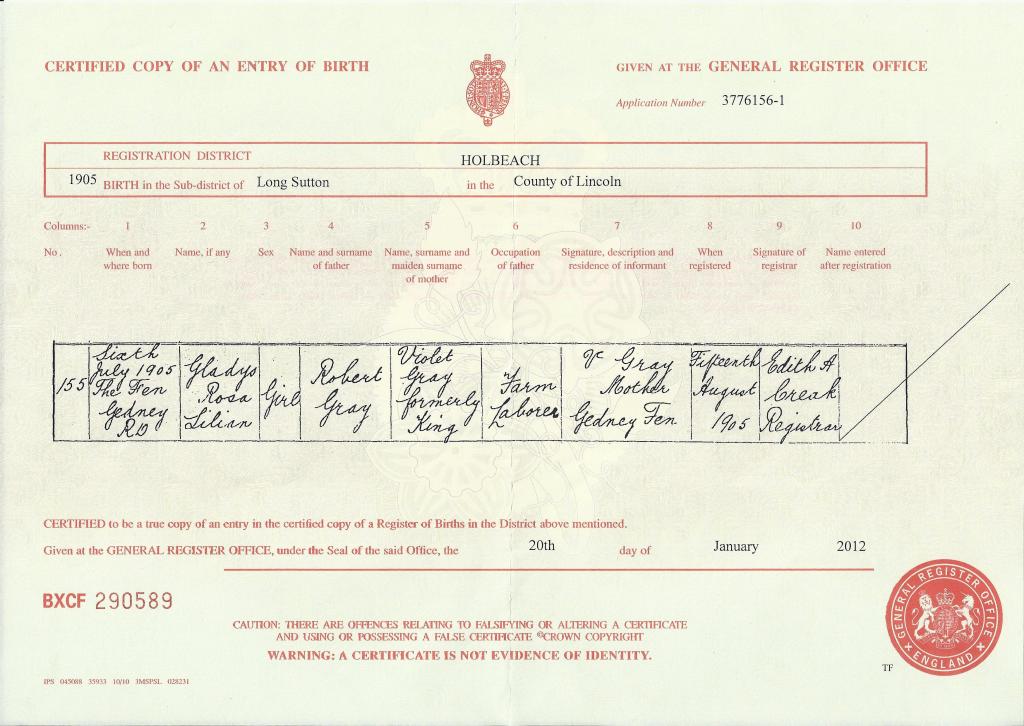

Gladys Rosa Lillian Gray was born on 6 July 1905 in Gedney, a parish in the South Holland district of Lincolnshire. The daughter of Robert Gray, a 24-year-old farm labourer, and Violet Gray (née King), aged 25, she entered a world defined by soil, weather, and work. Her birth was registered at Holbeach, and the family lived at Tydd Gote, an isolated agricultural hamlet whose residents depended on the land for survival.

Life in the Fens was harsh but steady. Families like the Grays worked the reclaimed flatlands — wheat, oats, beans, potatoes — for meagre wages that barely sustained them through the year. Farm labourers’ cottages were often “tied” to employment, meaning the family could lose their home if a job ended. Seasonal employment, long hours, and instability were a fact of life.

Gladys’s family likely participated in the agricultural gang system, a form of itinerant labour where women and children travelled with “gangmasters” from farm to farm to plant and harvest. Though partially regulated by the 1867 Agricultural Gangs Act, the system persisted into the twentieth century — and it was within this transient rural world that Gladys spent her early years.

A Rural Childhood of Movement and Hardship

In later years, Gladys’s daughter Connie (Constance Violet Marie Whalley) recalled her mother’s early life vividly in an interview conducted in 2011. Her words give rare, first-hand texture to the historical record.

Interview Callout: Connie on Her Mother

“My mum was from the country, so she was based on the farm all the time, and she liked farming with her mum. She just moved around a lot — like gypsies.”“She used to take fits, and I was the strongest out of the whole family. It needed a man’s strength to hold her down. I was more or less at home all the time.”

“We met up at the train after evacuation and there was my mum, looking gorgeous — she had lovely curly hair then. Later, when I brought my baby home, she had a big fire and cakes ready for me. I was treated like a queen.”

Connie’s recollections illuminate the realities of Gladys’s life — her love of farming, her ill health (likely epilepsy), and her maternal warmth despite constant hardship. Gladys’s seizures would have been frightening and poorly understood at the time. Early-twentieth-century medicine offered little sympathy or treatment; “fits” were stigmatised, often labelled as hysteria or moral weakness. Families frequently moved to escape gossip or discrimination — perhaps part of why Gladys’s family led such a mobile life.

Education for girls like Gladys was secondary to survival. With work and care duties taking precedence, she likely received minimal schooling. But she gained the kind of resilience that would define her life — practical, stoic, and fiercely devoted to her family.

First Marriage: Leonard Charles Osborne (1924–1932)

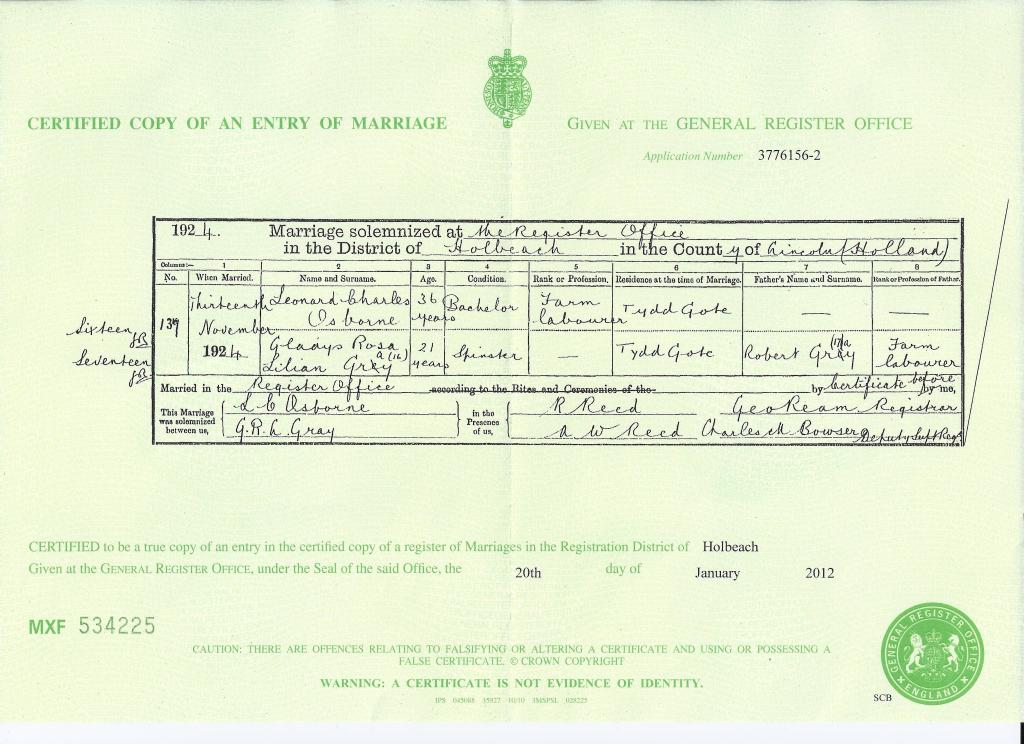

At 19, Gladys married Leonard Charles Osborne, a 36-year-old farm labourer, at the Holbeach Register Office on 17 November 1924. The witnesses were J. G. Osborne and G. R. L. Gray. For a young woman from the Fens, marriage to a stable labourer offered a rare promise of permanence.

Over the next few years she bore two daughters — Joyce Margerite (1925) and Mary Rose Irene (1927) — each born into the rhythm of seasonal work and rural poverty. By the early 1930s, however, Gladys’s life had changed dramatically. The birth of a third child, Muriel (around 1930), likely marks the beginning of her long relationship with John Joseph Howey, not a continuation of her marriage to Leonard Osborne.

This transitional period explains later confusion over surnames on official records. When Constance was born in 1932, her birth was still registered under the surname Osborne — reflecting Gladys’s legal marital status — even though both Muriel and Constance were John’s biological daughters. The use of Osborne on Constance’s certificate was therefore a legal technicality rather than a reflection of family reality.

Liverpool and Life with John Joseph Howey (1932–1967)

By the early 1930s, Gladys had met John Joseph Howey, a man whose own early life had been marked by upheaval. Born in Liverpool in 1898, John had been sent to Canada as one of Britain’s “Home Children,” forced into agricultural labour abroad before returning to England after the First World War.

When Gladys and John met, she was still legally married to Leonard Osborne. Divorce was prohibitively expensive and socially condemned in working-class communities, so formal separation was rare. Children born to married women were legally registered under their husband’s surname, regardless of paternity — which explains why Constance’s birth certificate lists her as Osborne, though her biological father was John Howey.

Together, Gladys and John built a partnership that would last 35 years and produce five children: Constance (1932), John (1937), Shirley (c.1937), David (1940), and Brenda (1948). They settled in Liverpool, part of a wider migration of families from the declining agricultural counties into industrial cities during the 1930s.

Wartime Motherhood

During the Second World War, Liverpool became one of Britain’s most heavily bombed cities. Gladys, now raising a large family, faced the daily terror of air raids while John served briefly in the military before being demobilised in 1940.

Her daughter Connie’s testimony offers a glimpse into this period:

“When the war came, I cried so much to go with Joyce when they were evacuating us. We got sent to Old Colwyn and Colwyn Bay, but we got separated. Then one day we looked out and there was my mum — she came to take us home. She looked gorgeous with her lovely curly hair.”

These small moments — a mother’s arrival at a railway station, a child’s relief — speak volumes about Gladys’s strength and devotion amid chaos.

Marriage After Three Decades (1963)

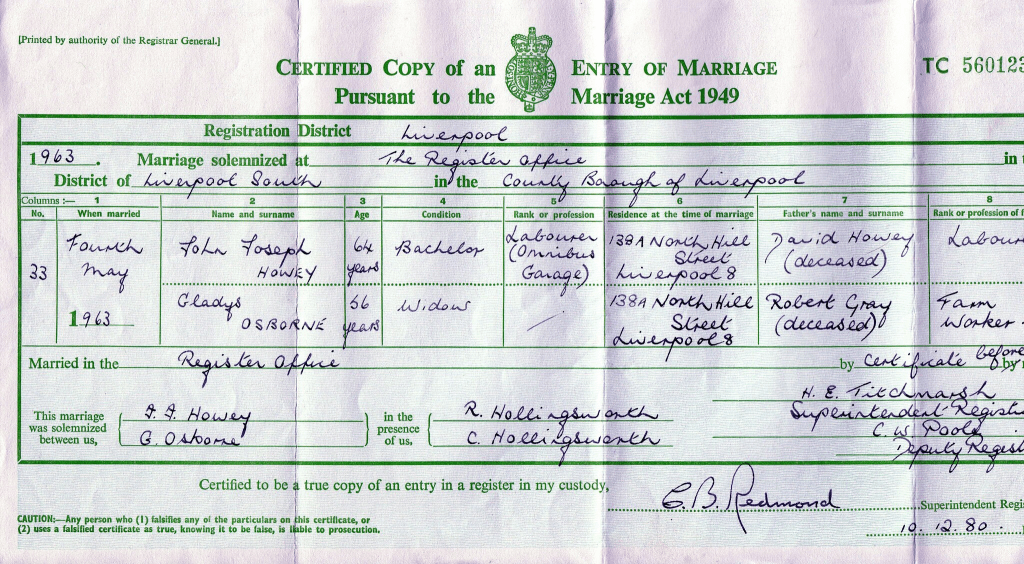

After more than 30 years together, Gladys and John were finally able to marry on 4 May 1963 at the Liverpool South Registry Office. She was 57; he was 64. Their daughter Constance and her husband Ronald Hollingsworth witnessed the ceremony — a symbolic moment that united the family across generations.

Both Gladys and John were recorded as “spinster” and “bachelor” on the certificate, a legal fiction that nonetheless closed a long chapter of irregular but enduring partnership. They had waited decades to make official what had long been true in spirit.

Tragically, their marriage was short-lived. John died in 1967, just four years later, aged 68. Gladys, widowed at 61, had lost the man with whom she’d shared more than half her life.

Final Years and Death (1967–1979)

Gladys lived quietly in Liverpool for the next twelve years. She remained at 5 Stonedale Crescent, the same address recorded on her marriage certificate. By then, her children were grown with families of their own.

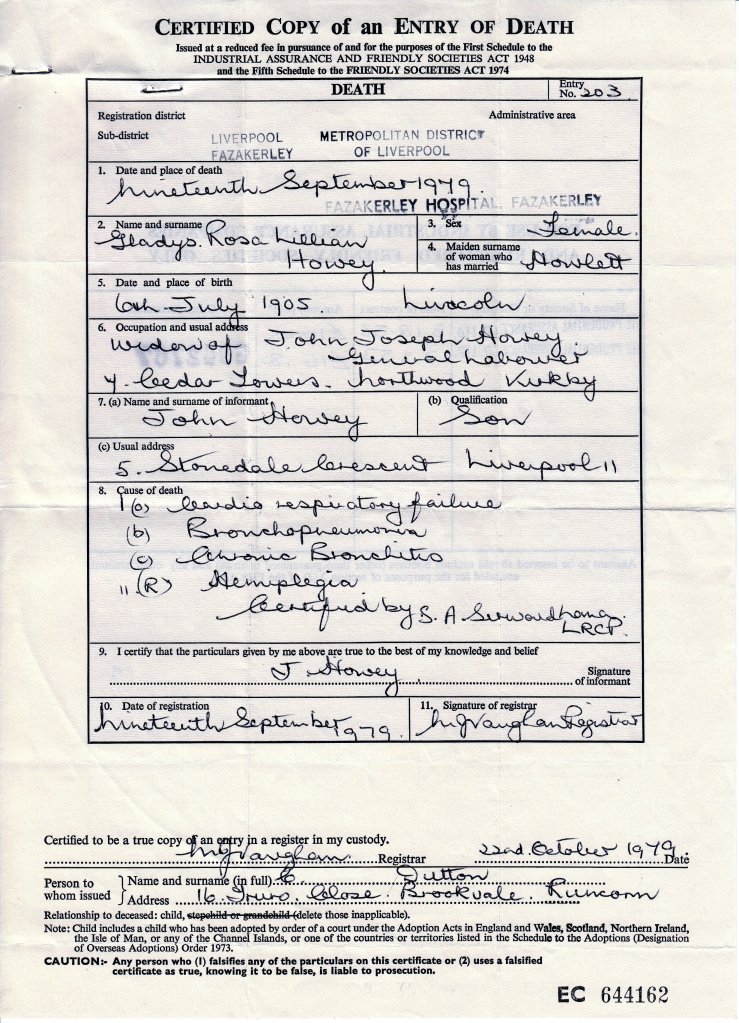

She died on 19 September 1979 at Fazakerley Hospital, aged 74. Her death certificate lists the causes as cardiac and respiratory failure following bronchopneumonia and chronic bronchitis — conditions common among working-class Liverpudlians exposed to poor housing and air quality.

Her obituaries, published by her daughters Joyce and Shirley, were simple but full of love:

“Thoughts go back to happy days when we were all together — the family chain is broken now, but memories live forever.”

“I have searched for the words to say how I feel; the words don’t come, but the tears do. So I will just say I love you, mam, so much — till we meet again.”

Legacy

Gladys’s life tells a story of endurance and transformation — from the muddy farmlands of Lincolnshire to the terraced streets of Liverpool, from an unrecorded farm labourer’s daughter to the matriarch of a large urban family.

She lived through poverty, stigma, and loss, yet left behind children who remembered her as loving, hardworking, and strong. Connie’s interview captures her best — a woman who made a home wherever she was, who “liked farming with her mum,” who looked “gorgeous” even after years of struggle, and who treated her daughter “like a queen.”

In the end, Gladys’s story — like so many working-class women’s — was not one of privilege or recognition, but of quiet, unyielding resilience. Her life, recorded across fragments of official documents and family memory, is a testament to the enduring strength and humanity of ordinary people navigating extraordinary times.

Hi Ann-Marie, I’m genuinely sorry that this has upset you. The site is very much a work in progress and…

This is disgusting, as a part of this family it’s incredibly inaccurate. Very jaded and entirely inappropriate you have not…

Leave a comment