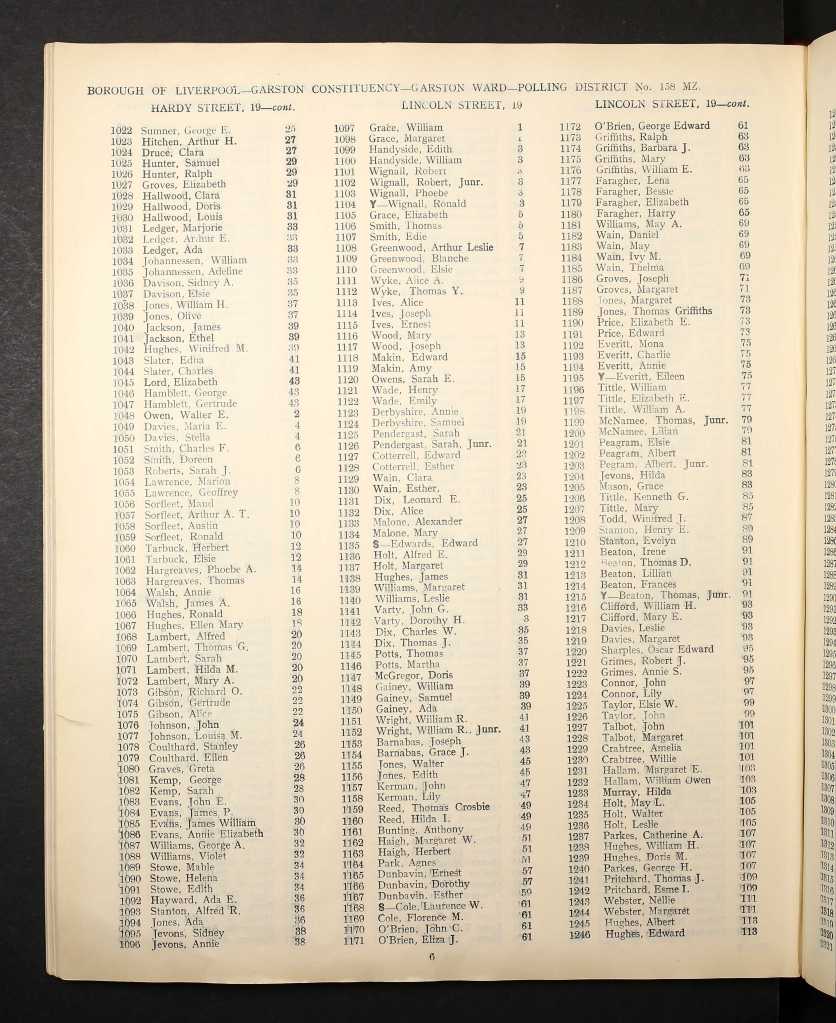

Born 1925, Garston, Liverpool

Mona Everitt was born in 1925 on Derby Street in Garston, Liverpool — a community of narrow streets, corner shops, and coal fires. Her parents had just married and were living in rooms near the village. From the start, she stood out. Her family called her “Cinderella” because she was “always by the fire,” warming her chilblained hands and feet. It was an affectionate nickname that captured her early years — tough, modest, but filled with love.

When Mona was barely a year old, illness struck. She was sent to hospital with stomach trouble and stayed there for eight months. During that time, her brothers at home came down with measles, so when she finally recovered, she couldn’t return home straight away. Instead, she went to stay with her Aunt Elsie in Wavertree. It was an early lesson in resilience that shaped the strong, self-reliant woman she would become.

Her earliest memory was of splitting her chin open at nursery while playing “bell horses” on a polished floor. She could still recall the stitches, the scolding nurse, and the itch she wasn’t allowed to scratch.

Growing Up in Garston

Life in Garston during the 1930s was simple but full of character. Mona remembered that her family home was peaceful — “there were never any rows in the house — never.” If someone misbehaved, punishment was gentle but firm: losing her Saturday halfpenny or penny. “That was enough,” she said. “You didn’t need more than that.”

Her Saturday penny was precious. She’d buy the biggest sweets she could find, though her mother always took one and placed it carefully on the sideboard, untouched for days. “It taught us to give,” Mona explained, “and not to just ask once.”

Poor eyesight ran in the family, and Mona inherited it from her father’s side. Her mother had suspected something was wrong since nursery, but doctors dismissed her concerns as “just habit.” It wasn’t until a specialist on Rodney Street examined her that the truth came out. “He said he’d never seen a child with such bad eyesight in all his life,” Mona recalled. “He wiped the floor with my father.” She laughed telling it, but it had been a turning point.

Because of her vision, Mona attended a special open-air school for children with poor sight. Her class ranged in age from seven to sixteen, and instead of sports or traditional subjects, she excelled in crafts — basket weaving, knitting, painting, and stool making. “Even now,” she said proudly, “if somebody gave me the base and the cane, I could make a tray.”

Mona couldn’t play games or bend down to touch her toes, but she found joy in quieter activities. In the evenings, she and her siblings would paint, tracing outlines with fine black brushstrokes to make their work stand out. They shared the washing up, too — “one washed, one dried” — taking turns without argument. It came naturally, she said.

She had hoped to train as a children’s nurse, but the family couldn’t afford the fees. Instead, she went to work caring for children, calling it “the next best thing.”

Teenage Mischief and Wartime Memories

As a teenager, Mona wasn’t above a bit of mischief. At thirteen, she and a friend used a penny tram ticket to go into Liverpool without permission — and she still laughed at the memory of sprinting home past Garston Parish Church at half-past nine, knowing her mother would be furious.

The Second World War changed everything. At fourteen, Mona was evacuated to Holywell, North Wales, while her siblings were sent elsewhere. She stayed first with Miss Jones, a retired postmistress who became a cherished figure in her life. Mona even knitted her a tea cosy as a gift. When her family tried to bring her home, she told the headmaster she wanted to stay — and did so until she was sixteen. “If I’d got a job,” she said, “I’d have stayed there forever.”

Love and Marriage

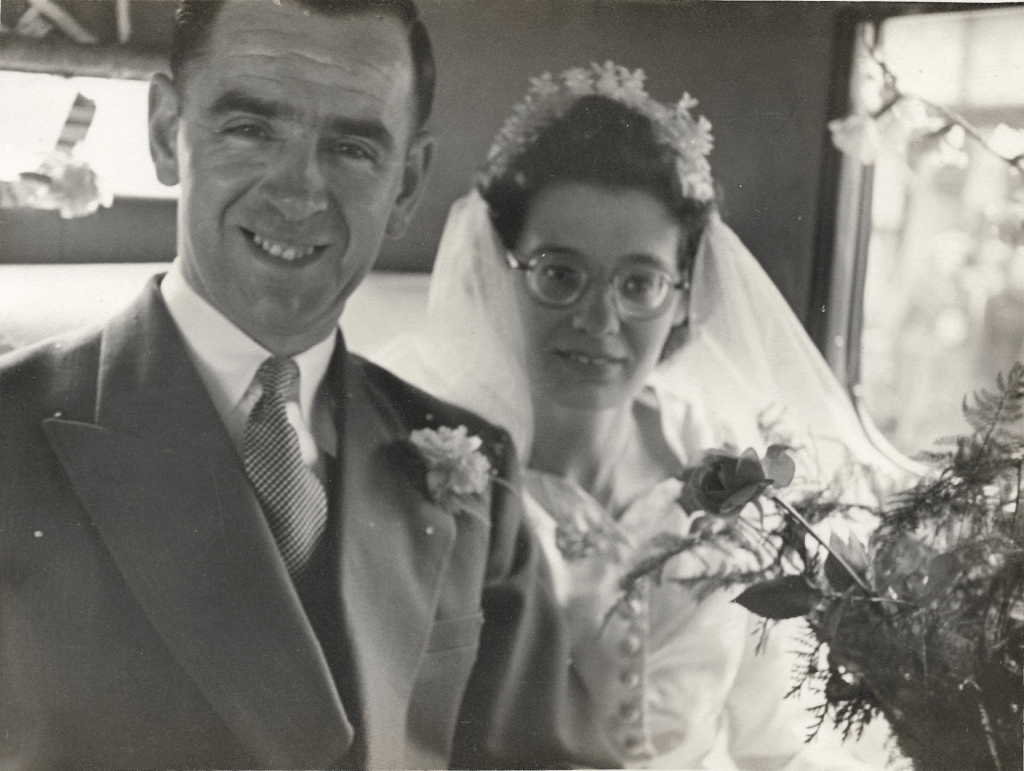

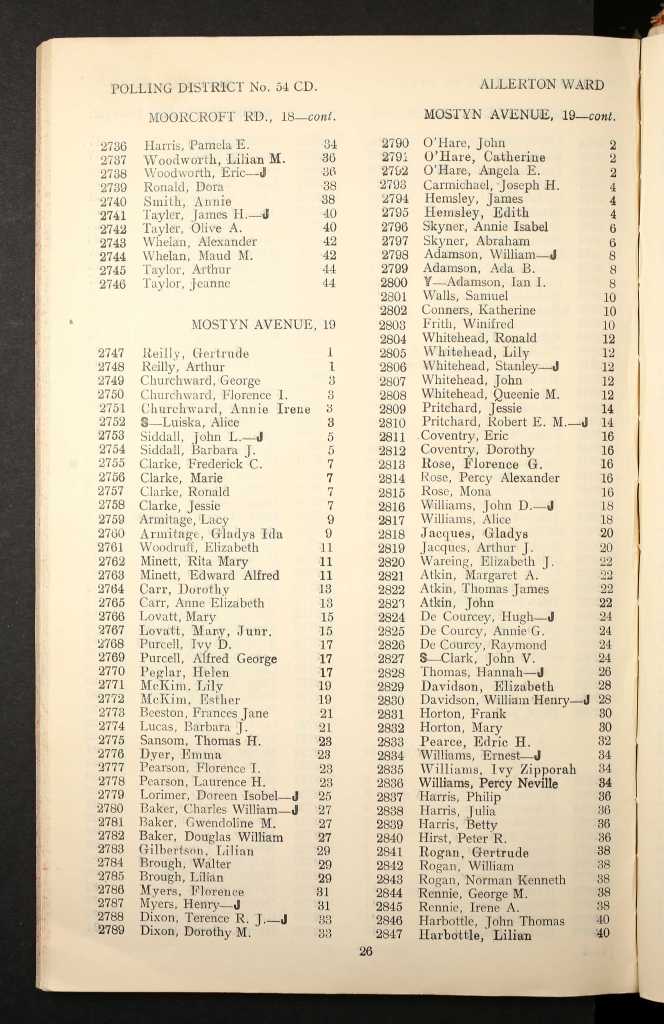

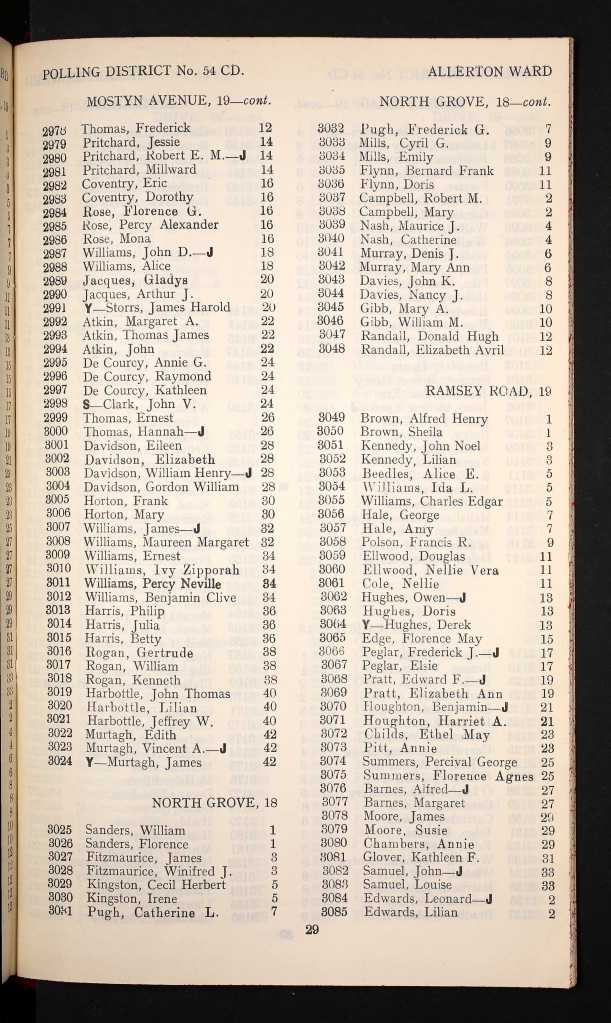

After the war, Mona’s life took a romantic turn. She met her future husband, Percy Rose, when he knocked on her door each week as the family’s insurance agent. One day, she noticed the Speedway badge on his jacket and admitted she’d never been to a race. He offered to take her — and that became their first date, at Edge Lane’s Stanley Track.

Their courtship was sweet and full of laughter. They went to wrestling matches at Garston Baths, to her father’s amusement: “I never thought a child of mine would go and watch wrestling,” he told her.

Percy eventually proposed on a bench in Garston Bowling Green, and the two serenaded each other — Percy singing “Bless You for Being an Angel,” Mona replying with “Yours Till the Stars Lose Their Glory.”

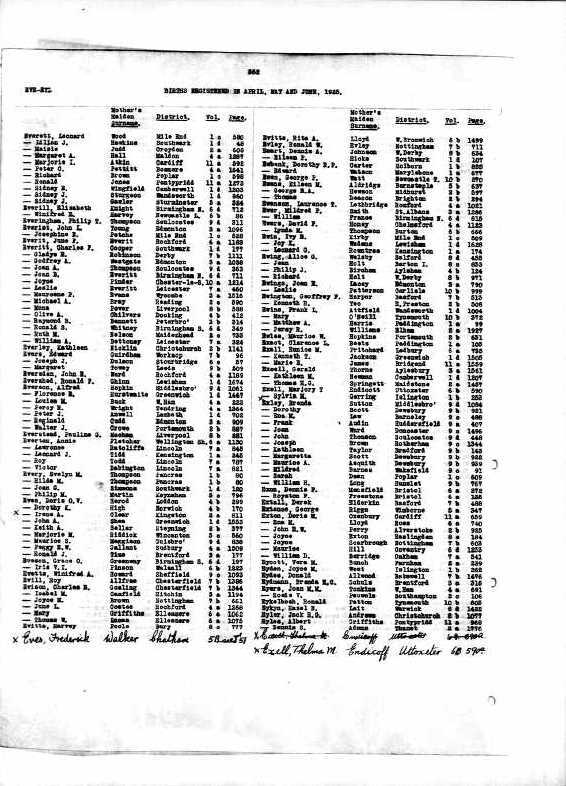

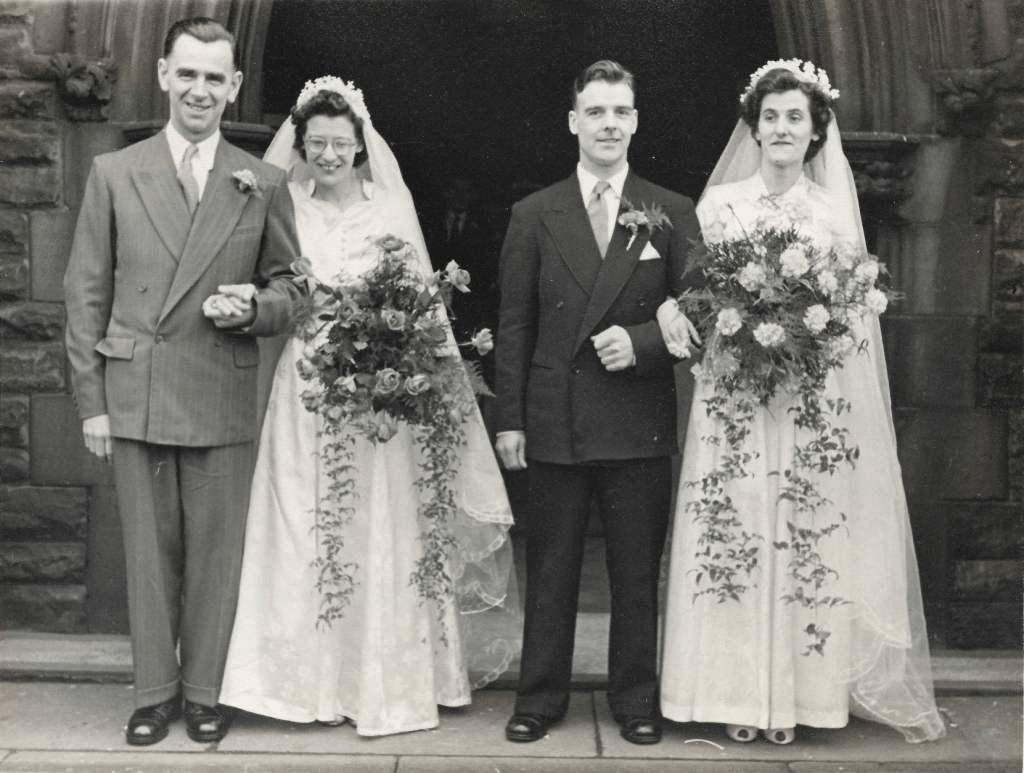

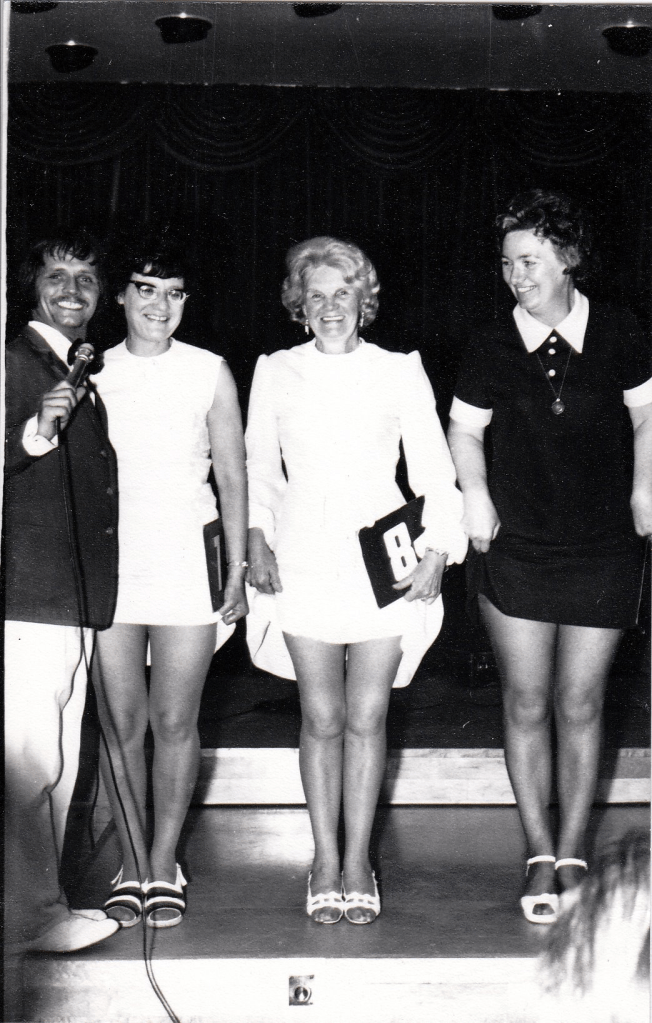

Mona and Percy married on 23 February 1952 at Garston Parish Church in a joint ceremony with Mona’s sister, Eileen and her husband, Arthur. Their wedding day was filled with laughter, including her hiding among the guests to avoid dancing the tango with her brother-in-law Billy, while everyone pointed her out.

Family Life and Motherhood

Mona described Percy as “lovely, a bit shy at first, but we soon brought it out of him.” They built a warm, steady life together, rarely arguing. “In forty-three years of marriage,” she said, “we only had two disagreements, and never went to bed on an argument.”

Motherhood was one of her proudest achievements. When her son was born, he was taken to Alder Hey Hospital with suspected bowel trouble. She cried herself to sleep that night, but he soon returned home — stronger than ever. When nurses doubted her milk was enough, she replied with a smile, “It’s not quantity, it’s quality.” They later nicknamed him “King Ted,” though Mona never quite knew why.

Her daughter arrived later, but feeding was harder — the hospital supplements, she said, “turned it to water.” Still, she persevered, full of quiet humour even in difficulty.

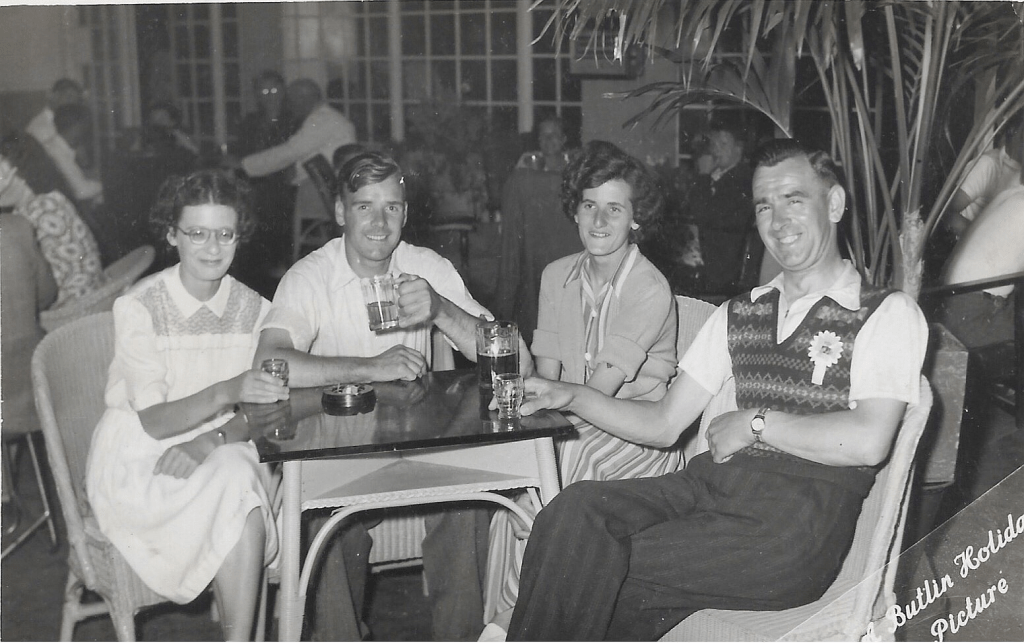

Mona’s home was full of warmth, love, and laughter. She and Percy took the children on caravan holidays to Rhyl and Towyn, sometimes waking to flooded campsites after heavy rain. “In those days,” she laughed, “you took everything with you — a big case full of food, apart from all the other stuff.”

Later Years and Reflections

In her later years, Mona often reflected on how much the world had changed. She worried that “people are crying poverty” while governments “line their own pockets,” and she missed the discipline and respect of earlier generations. Yet her humour never faded. She recalled stopping a screaming child in a shop simply by saying, “That’s a funny noise,” and watching him instantly fall silent.

She spoke lovingly of her grandmother, a gentle woman she adored who died after being hit by a lorry in Padgate. “You could say, ‘Grandma,’ and she’d reply, ‘Yes, my dear,’ just like that.” Her memories of her grandmother and Aunt Emma — “like a little doll, you were afraid to hug her in case you crushed her” — were among her most tender.

She also remembered a family legend — that the Everitts were distantly connected to the artist J.M.W. Turner and Sir Henry Tate of Tate Gallery fame. “That’s what my mother told me,” she said with a shrug. “I don’t know if it’s true, but it’s a nice thought.”

And, tucked away in her memories, there was once a beautiful old family Bible with brass clasps and gold-edged pages — a symbol of faith and continuity. Mona thought it might still be with her sister Eileen’s family.

When asked what she wanted people to remember about her, Mona laughed and said simply:

“Doing things that we shouldn’t do.”

Beneath that cheeky answer was her true legacy — warmth, humour, courage, and love.

Death, 2021, Warrington.

Mona passed away peacefully in Warrington on 4 October 2021, aged 96, following a gradual decline in health due to frailty and hypertension. She was remembered for her deep compassion and unwavering love of family.

Hi Ann-Marie, I’m genuinely sorry that this has upset you. The site is very much a work in progress and…

This is disgusting, as a part of this family it’s incredibly inaccurate. Very jaded and entirely inappropriate you have not…

Leave a comment