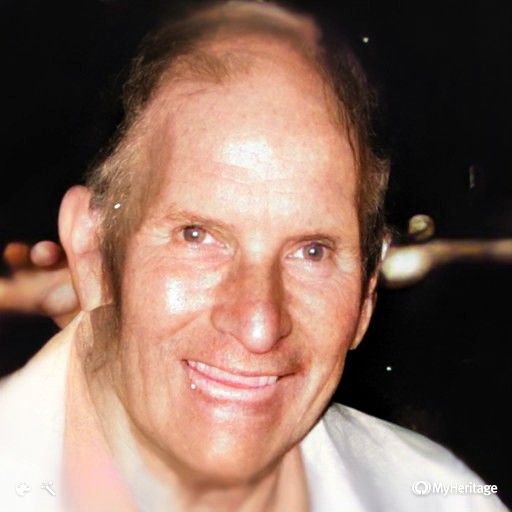

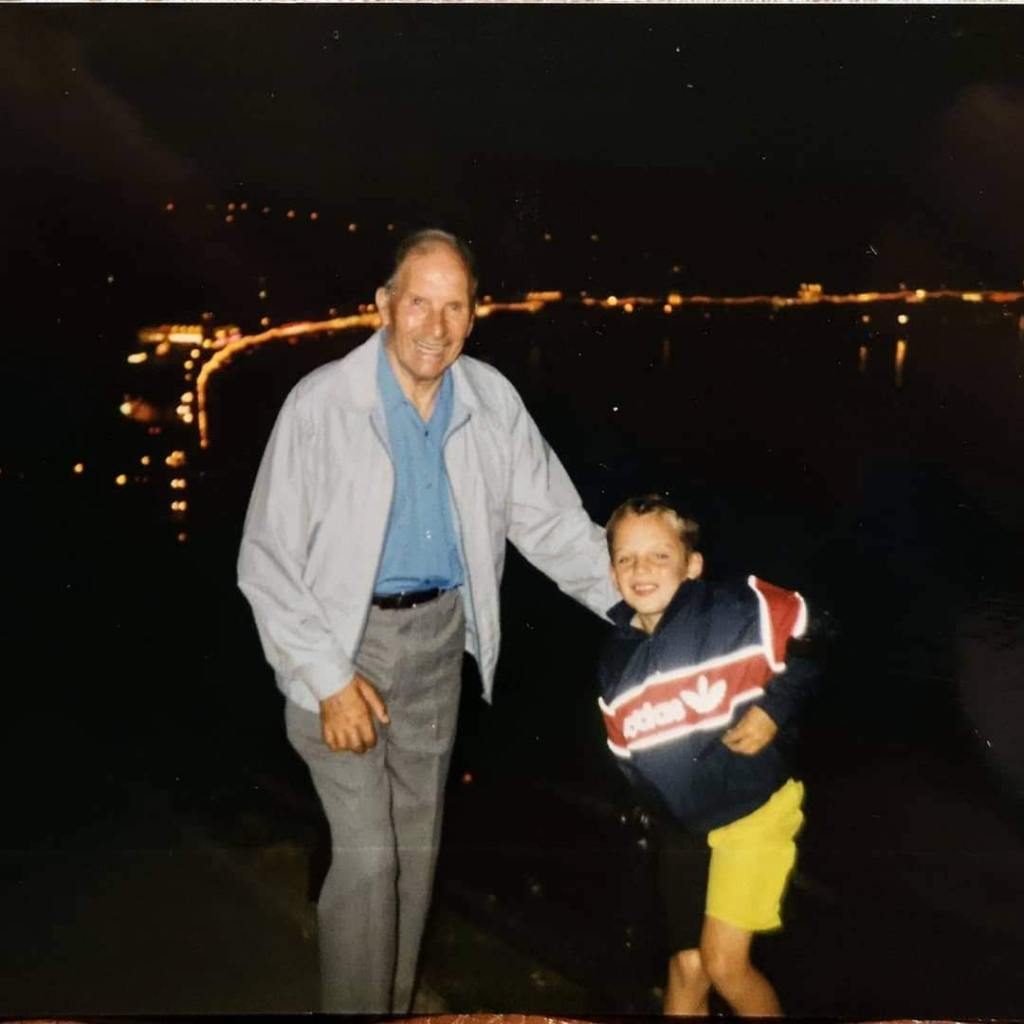

Thomas (Tom) Dutton was my step-grandad, affectionately known to me as ‘Grandad Tom’, married to my nan, Constance (Connie) Violet Marie Dutton (née Howey, later Hollingsworth / Whalley). To me, he’s one of those figures who represents the kind of quiet, steady strength that built the towns along the Mersey: the men who went to work every day in the chemical plants and factories, who served their country when called, and who carried the marks of those years in the lines of their faces and the set of their shoulders. Tom lived his whole life in Runcorn, a town that grew up around industry, shaped by its factories, canals, and hard graft.

Early Life in Runcorn

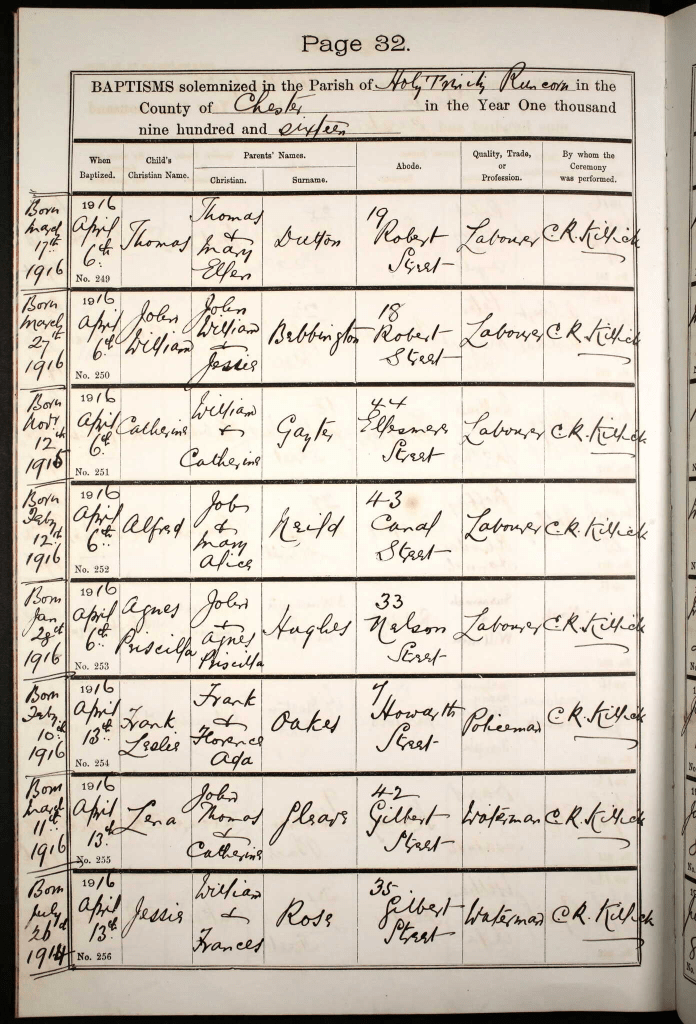

Thomas Dutton was born on 17 March 1916, right in the middle of the First World War. His baptism took place soon after at Holy Trinity Church in Runcorn, a parish that served much of the local working-class population at the time. His parents were recorded as Thomas Dutton, a labourer, and Ellen (or Mary Ellen, as later records show).

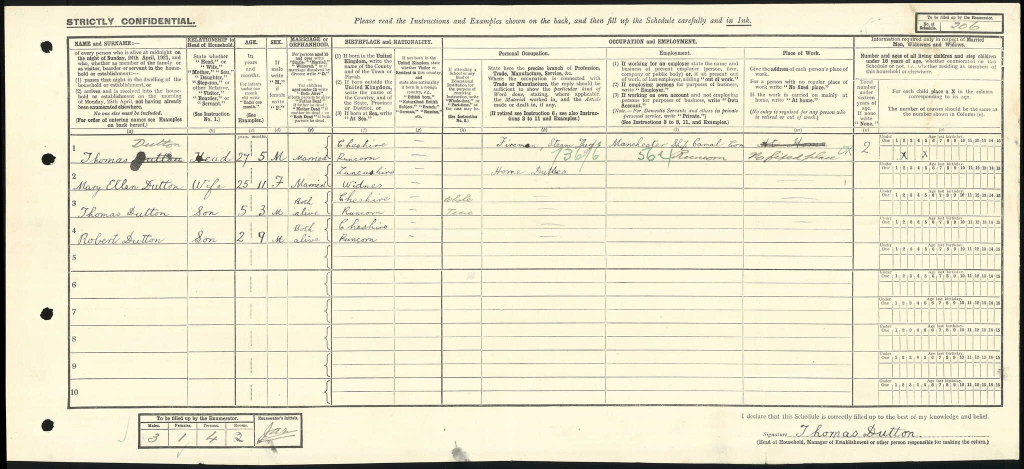

By the time of the 1921 census, Thomas was five years old and living with his mother and younger brother, Robert, who was just two. His father, Thomas, listed in that record as a Fireman working on the Manchester Ship Canal.

Runcorn itself, in the years of Tom’s childhood, was a place on the move. The docks and the chemical plants were booming, pulling in workers from across Cheshire and Lancashire. Families like the Duttons lived in modest terraced houses within walking distance of the factories or the river. The town’s skyline was dominated by chimneys, cranes, and canal bridges — an industrial backdrop that would define Tom’s life from beginning to end.

He would have gone to one of the local board schools, likely leaving education around 14 to start earning a wage, as most boys did. The idea of a long education wasn’t something working families could afford then; the expectation was simple — you left school and went to work. For Tom, that probably meant joining the same industrial rhythm that filled Runcorn’s streets with men in overalls, lunch tins in hand, heading for the shift change at one of the chemical works that lined the Mersey and the Ship Canal.

A Life Shaped by Industry

Tom’s adult working life is recorded most clearly through his death certificate, which lists him as a retired “chemical process worker.” That one line connects him directly to the huge industrial empire that once defined Runcorn. Companies like Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) were the town’s heartbeat. Their sprawling sites — Castner Kellner, Rocksavage, Weston Point — employed thousands. These plants produced everything from chlorine and caustic soda to PVC, ammonia, and dyes. They were the sort of places where generations of the same families worked side by side, often father and son, sometimes for life.

The work was heavy and dangerous. A “chemical process worker” was part of the teams who kept the production lines running: controlling reactions, monitoring vats and tanks, maintaining temperatures, valves, and pressures that could, at times, turn lethal if something went wrong. It was hard, physical labour, often done in heat and fumes, with little understanding back then of the long-term health effects. But for men like Tom, it was steady work with a decent wage — and, crucially, it was local. You didn’t need to leave Runcorn to make a living.

In the 1940s and 1950s, ICI was expanding fast. It was one of Britain’s biggest industrial employers, and Runcorn was one of its flagship centres. At its height, the Castner Kellner plant used as much electricity as the whole of Liverpool. To work there meant being part of something enormous — a vast machine that kept post-war Britain supplied with the chemicals that built everything from medicines to plastics. It also gave the town its particular smell, that mix of salt, chlorine, and smoke that people who grew up there still remember vividly.

For the families living around Weston Point, the factory whistle marked the rhythm of daily life: starting shifts, ending shifts, calling men to work at all hours. It’s easy to imagine Tom walking those same routes, maybe cycling down to the plant, his overalls rolled up and his lunch tin balanced on the handlebars. The sense of pride in that work was real — even if it was tough, even if it left its mark on the body.

The War Years

Tom was 23 when war broke out in 1939, and like most young men of his generation, he served. A 1946 Soldiers’ Release Book confirms his return to civilian life at the end of the war. Unfortunately, not much is known about where or how he served — his regiment and duties aren’t recorded in the surviving documents. But the very fact of his service places him among millions of British men who were uprooted from their normal lives and sent around the world between 1939 and 1945.

It’s likely he saw at least some of the hardships of wartime service: the long periods away from home, the rationing, the disruption of family life. And when he came back, he would have returned to a changed country — one where bomb damage and rebuilding shaped every street, and where men carried the quiet weight of what they’d seen. That experience of service often stayed with them in subtle ways: in discipline, in routine, in the value placed on steady work and modest living. In later life, people often remembered Tom as calm and practical — qualities that fit the mould of that wartime generation.

First Marriage and Family

The details of Tom’s first marriage are harder to piece together, but what’s known is that he married sometime in the years following the war and had two daughters, Phyllis and Linda. Records show that by 1977 he was listed as a widower, which means his first wife had died before then. Sadly, her name hasn’t yet been traced in surviving documents, though family knowledge confirms she existed and that the marriage was real and lasting enough to produce his two children.

Phyllis and Linda would have grown up in Runcorn or nearby, in the decades when the town was still thriving industrially. The 1950s and 60s were good years for working families: full employment, better wages, new council housing, and a sense that life was improving after the hardships of war. For Tom, those would have been years of stability — work at ICI, a home, and family life shaped by the routines of shift work and community ties.

Losing his first wife must have been a difficult period. Widowers of his generation didn’t often talk openly about grief, but the loss would have left a gap — especially for a man still working long shifts and raising two daughters. It says something about his resilience and sense of responsibility that he carried on, maintaining his job and caring for his family through those years.

Marriage to Connie and the Blended Family

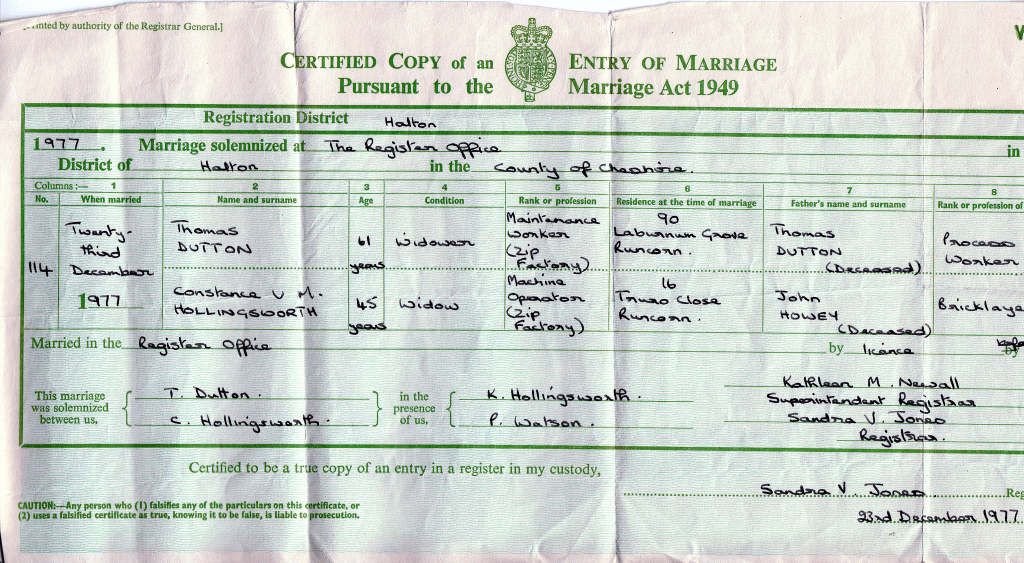

On 23 December 1977, at the age of 61, Tom remarried. His bride was my nan, Constance Violet Marie Howey — though by that point she was known as Connie Hollingsworth, the name of her first husband, Ronald. They married at the Register Office in Halton, just two days before Christmas, a time of year that would always after carry that memory of a new beginning.

The certificate paints a clear picture of the couple at that time. Connie was 45, described as a “machine operator (zip factory),” working at what was likely the local YKK Zip Company. Tom was a “maintenance worker,” still involved in hands-on industrial work. Both were working-class to the core, used to long hours and practical living. Their shared background probably gave them a quiet understanding of each other’s lives — no pretence, no grandeur, just honest work and companionship.

Their address was listed as 90 Laburnham Grove, Runcorn, a modest house in a typical suburban estate of the period, although by the early-1980s they had relocated to 16 Truro Close, noted as Connie’s residence on the marriage certificate. These were new homes compared to the old terraces of earlier generations, often with small gardens and driveways — symbols of post-war progress.

Through Connie came her son, Keith, my mum’s side of the family. The relationship meant that Tom became part of our story too — not by blood, but through marriage and the bonds of shared family life. He wasn’t a man of big gestures or showy words, but from my experiences, the sort of step-grandad who was just quietly there: solid, dependable, part of the family fabric.

Health Decline and Motor Neurone Disease

In the late 1980s, Tom was diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease (MND), a cruel and progressive condition that affects the nerves controlling muscle movement. It’s a disease that strips away physical strength while leaving the mind intact, one of the hardest combinations imaginable. For someone who had spent a lifetime working with his hands — a man used to fixing, carrying, maintaining — the gradual loss of mobility must have been devastating.

The family moved to a bungalow during this time, a practical step that allowed him to live more comfortably as the illness advanced. Bungalows were a typical adaptation for MND patients: no stairs, easier wheelchair access, and room for aids and medical equipment. It’s a detail that speaks volumes about the kind of family support Tom had — and the quiet care that surrounded him in those years.

MND was less well understood then than it is today. There was little that doctors could do beyond managing symptoms, and the emotional and physical toll fell heavily on both patient and carers. Connie was known for her strength and compassion, and it’s easy to picture her caring for Tom with the same calm resolve that characterised her life.

The connection between industrial work and neurological disease is something that’s been studied more closely in recent decades. Men who worked in chemical processing, like Tom, were often exposed to solvents and gases that we now know can have long-term health effects. While we can’t say for sure that his work contributed to his illness, the link between occupational exposure and conditions like MND has been noted in medical research. For many industrial workers of his generation, the hazards of the job were invisible until much later in life.

Death and Farewell

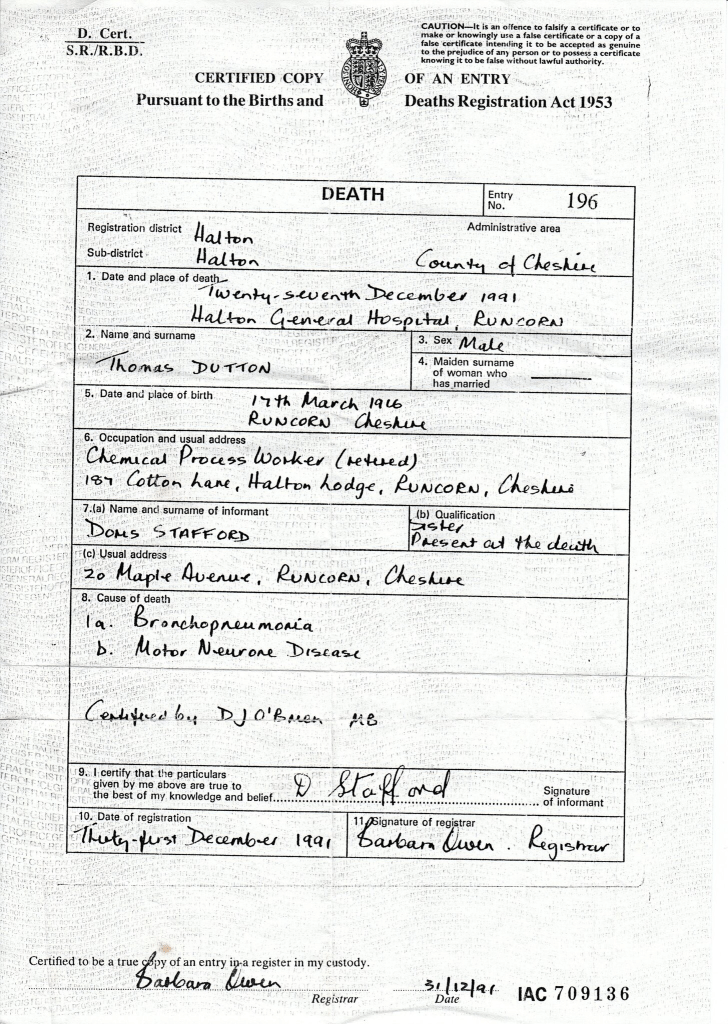

Tom died on 27 December 1991 at Halton General Hospital in Runcorn, aged 75 — just four days after Christmas.

His sister, Doris Stafford, was by his side. The causes recorded on his death certificate were bronchopneumonia and Motor Neurone Disease. Halton General was a relatively new hospital at that time, having opened in stages from 1976, and it would have been the main local facility for the town’s residents. Dying there, close to home, surrounded by family, brought his life full circle — the same town he’d been born in 75 years earlier.

The funeral was held at St Andrew’s Church on Festival Way, followed by cremation at Walton Lea Crematorium. The arrangements, were handled with care and dignity, reflecting the family’s wish to give him a proper farewell. A small but telling note appears in the funeral paperwork: the first invoice mistakenly listed his name as “William Dutton.” Connie had it corrected before sending a copy to his daughters and their families in Australia. It’s one of those ordinary details that somehow humanises everything — the small administrative hiccups that sit beside the deep emotional moments of life and death.

Legacy of Work and Place

Tom’s story, like so many of his generation, is deeply bound up with the history of Runcorn itself. Born in a town defined by heavy industry, he worked through its peak years and lived long enough to see it begin to change. In 1964, Runcorn was designated as a “New Town,” bringing modern housing estates and new transport links, but also signalling the decline of traditional employment. The huge ICI plants that had once provided lifetime careers started to contract by the 1980s, and the communities built around them began to shift.

For Tom, whose entire identity had been tied to that industrial world, those changes would have been bittersweet. The sense of pride and belonging that came from working in a major chemical works wasn’t just about wages — it was about purpose, camaraderie, and shared experience. When people from that era look back, they often talk about the strength of community: everyone knowing each other, streets filled with workmates, families bound by the same factory shifts. Tom’s life fitted squarely within that world — one that was disappearing even before he passed away.

Remembering Tom

Although I only knew him as a young child myself, I’ve come to understand my Grandad Tom through the documents and the stories that survive — his birth and baptism records, the census entries, the marriage certificates, his soldier’s release book, his medical card, and the funeral papers. Each one adds a small piece to the picture: the son of a labourer born into wartime Britain; the young man who served his country; the worker who helped power the chemical industries that built post-war prosperity; the widower who found love again late in life; and the patient who faced his final illness with quiet strength.

For my nan, Connie, their marriage was a defining chapter. They were together for fourteen years before his death, a period that spanned both ordinary domestic life and the challenges of serious illness. She would go on to live until 2020, reaching 88 years of age — nearly three decades after Tom’s passing. Her later remarriage to Keith Whalley in 2009 shows that she, too, found ways to keep living, loving, and adapting. But I like to think she always carried memories of Tom — of the years they shared in Truro Close, of the quiet routines of their life together, and of the care that marked his final chapter.

A Life that Speaks for Many

In many ways, Tom Dutton’s story is not one of dramatic events or grand achievements — and that’s precisely why it matters. His life was emblematic of the millions of ordinary working men who built the fabric of 20th-century Britain. They didn’t make headlines, but they kept the country running: manning the factory floors, maintaining the machines, serving when called, raising families, and facing life’s hardships without complaint.

Tom’s 75 years trace a full arc through British history — from the First World War through the Second, into the industrial boom and eventual decline that reshaped towns like Runcorn. His experience mirrors that of so many in the North West: born into a labouring family, educated just enough to work, drawn into heavy industry, married young, widowed, remarried, and carried through to the end by family ties and quiet endurance.

When I look at his story, I see not just one man’s life but a whole generation’s way of living — the values of hard work, loyalty, practicality, and love expressed not through words but through action. Tom may not have left behind diaries or speeches, but the traces of his life — the official papers and family recollections — tell a story that deserves to be remembered.

He was a son, a soldier, a husband, a father, a step-grandad. And though the factories that once defined his world have mostly disappeared, replaced by housing estates and business parks, his legacy still echoes in the families that remain, and in the memory of what Runcorn once was: a town built on work, community, and people like Tom Dutton.

Hi Ann-Marie, I’m genuinely sorry that this has upset you. The site is very much a work in progress and…

This is disgusting, as a part of this family it’s incredibly inaccurate. Very jaded and entirely inappropriate you have not…

Leave a comment