John Joseph Howey (1898–1967) lived a remarkable life shaped by the turbulent forces of twentieth-century history. Born in Liverpool during the Victorian era, institutionalized as a child, sent to Canada as a British Home Child, and serving in both world wars, his story epitomizes the experiences of countless working-class individuals whose lives were defined by displacement, hardship, and perseverance. This report draws upon baptismal records, military attestation papers, visitor reports, census data, and official service documents to construct a detailed account of his extraordinary journey.

Early Life and Family Origins in Liverpool

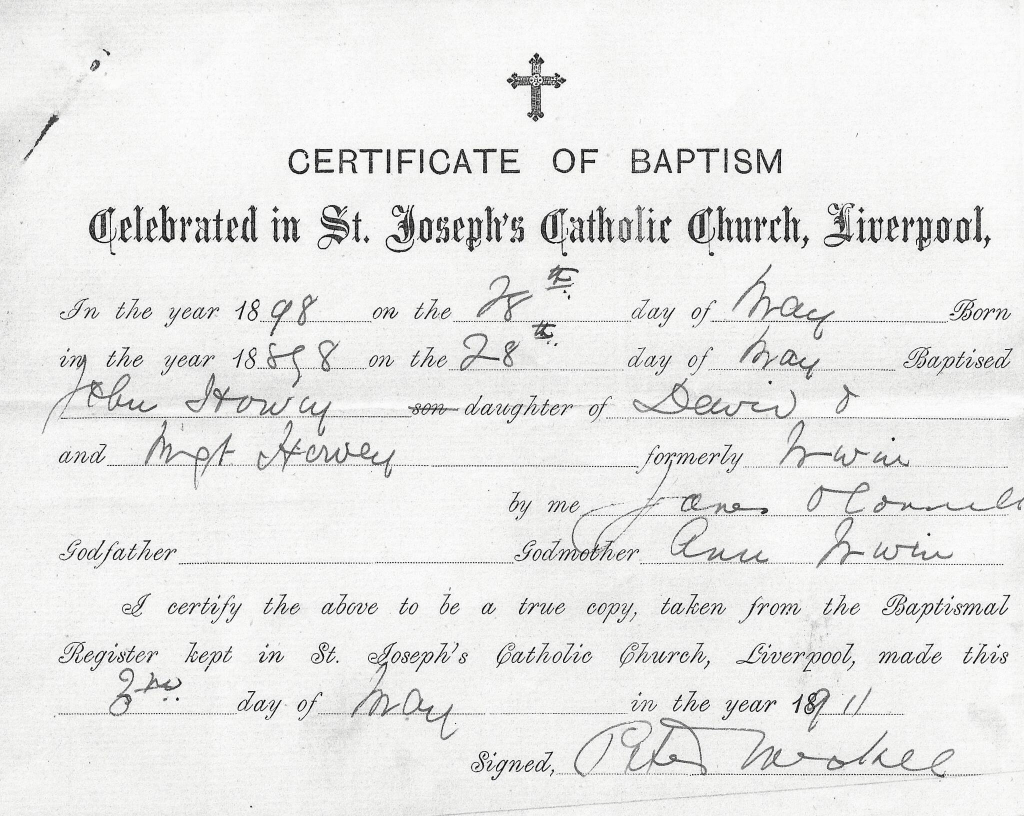

John Joseph Howey was born on 28 May 1898 in Liverpool, Lancashire, England, into a Roman Catholic family of modest means. His father was David Howey (born circa 1864), aged 34 at John’s birth, who originated from South Wales. His mother was Margaret Howey (née Irwin) (born circa 1870), aged 28 when John was born. According to his baptismal certificate from St Joseph’s Catholic Church in Liverpool, he was baptized on 28 May 1898.

Liverpool at the turn of the century was a bustling port city with significant Irish Catholic immigration, high levels of poverty, and a large population of children living in precarious circumstances. Many families struggled with unemployment, overcrowding, and disease, conditions that frequently led to children being placed in institutional care or emigration schemes. The Howey family appears to have faced such difficulties, with David residing in South Wales while Margaret and John remained in Liverpool—a geographical separation that suggests economic hardship and family disruption.

Childhood Difficulties and Institutionalization (1908)

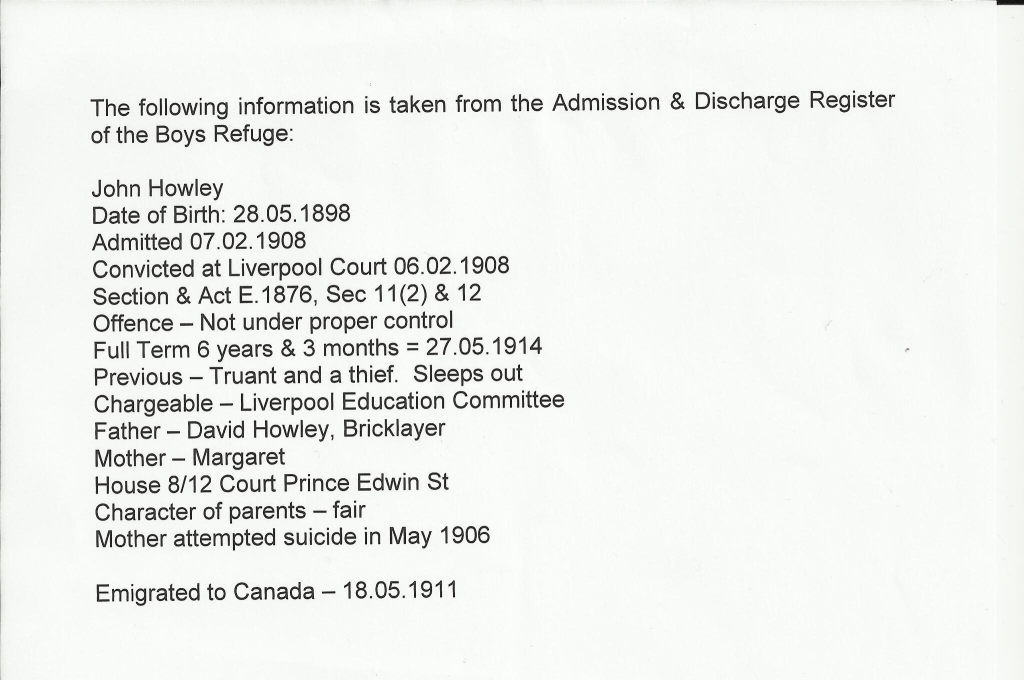

John’s childhood was marked by significant hardship and behavioural problems that reflected the desperate circumstances of many Liverpool children in the Edwardian era. In 1908, at just ten years old, John was sentenced to 6¼ years in a boys’ home for being “not under proper control”. The official record noted he had previous convictions as a truant, thief, and someone who sleeps out.

This harsh sentence—essentially detaining a child until nearly seventeen years of age—was characteristic of the punitive approach to juvenile delinquency prevalent in early twentieth-century Britain. “Sleeping out” (homelessness or running away) and truancy were often symptoms of family breakdown, poverty, or abuse, yet children were criminalized rather than supported. Industrial schools and reformatories, ostensibly designed to reform wayward children through discipline and training, often functioned more as punitive institutions that prepared working-class children for lives of manual labour.

This institutionalization would have profoundly shaped John’s childhood and likely contributed to his subsequent emigration to Canada as a British Home Child. Many children in reformatories and industrial schools were specifically targeted by emigration societies, which saw them as ideal candidates for agricultural labour overseas.

The British Home Child Experience (1911–1920)

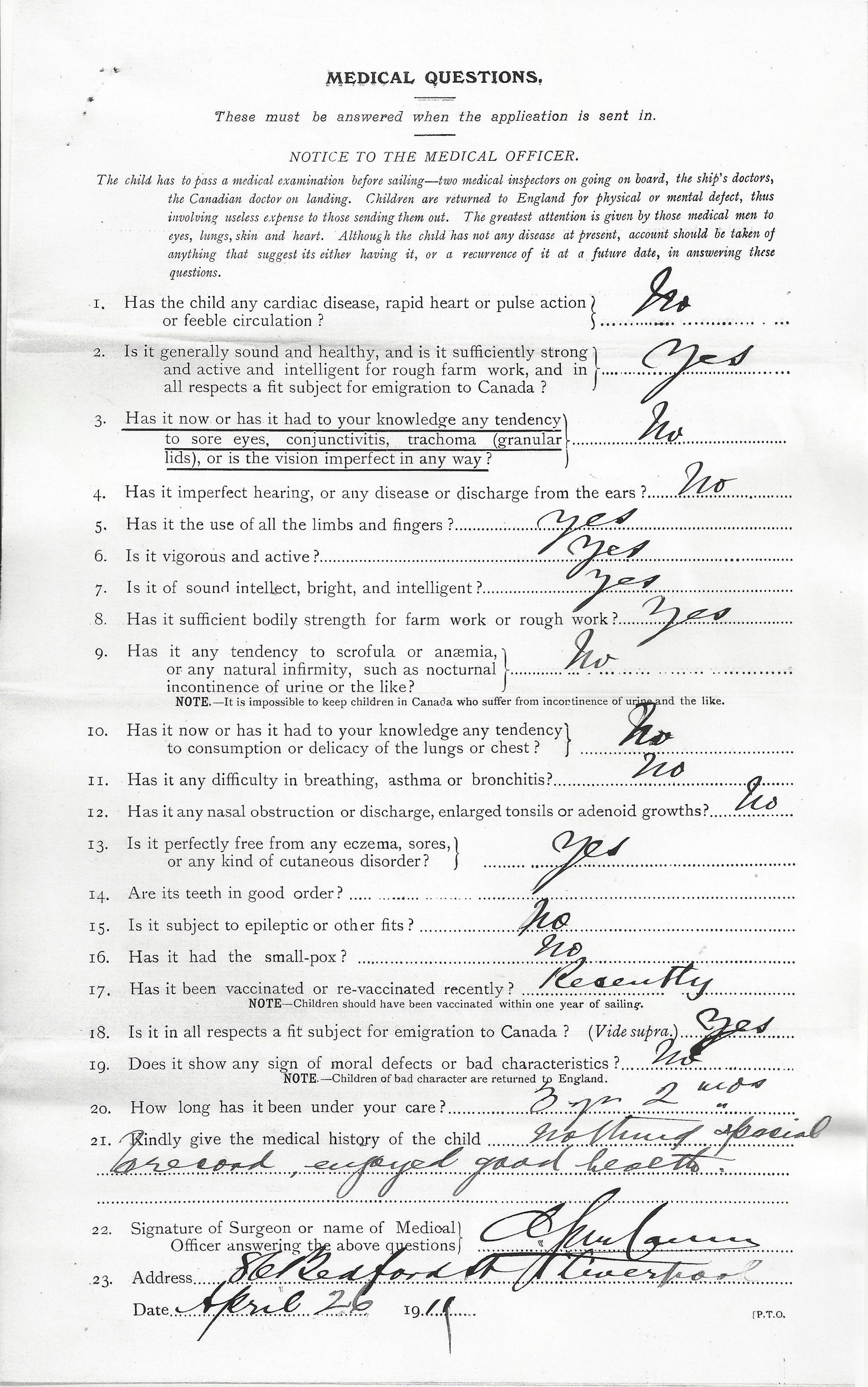

Emigration to Canada

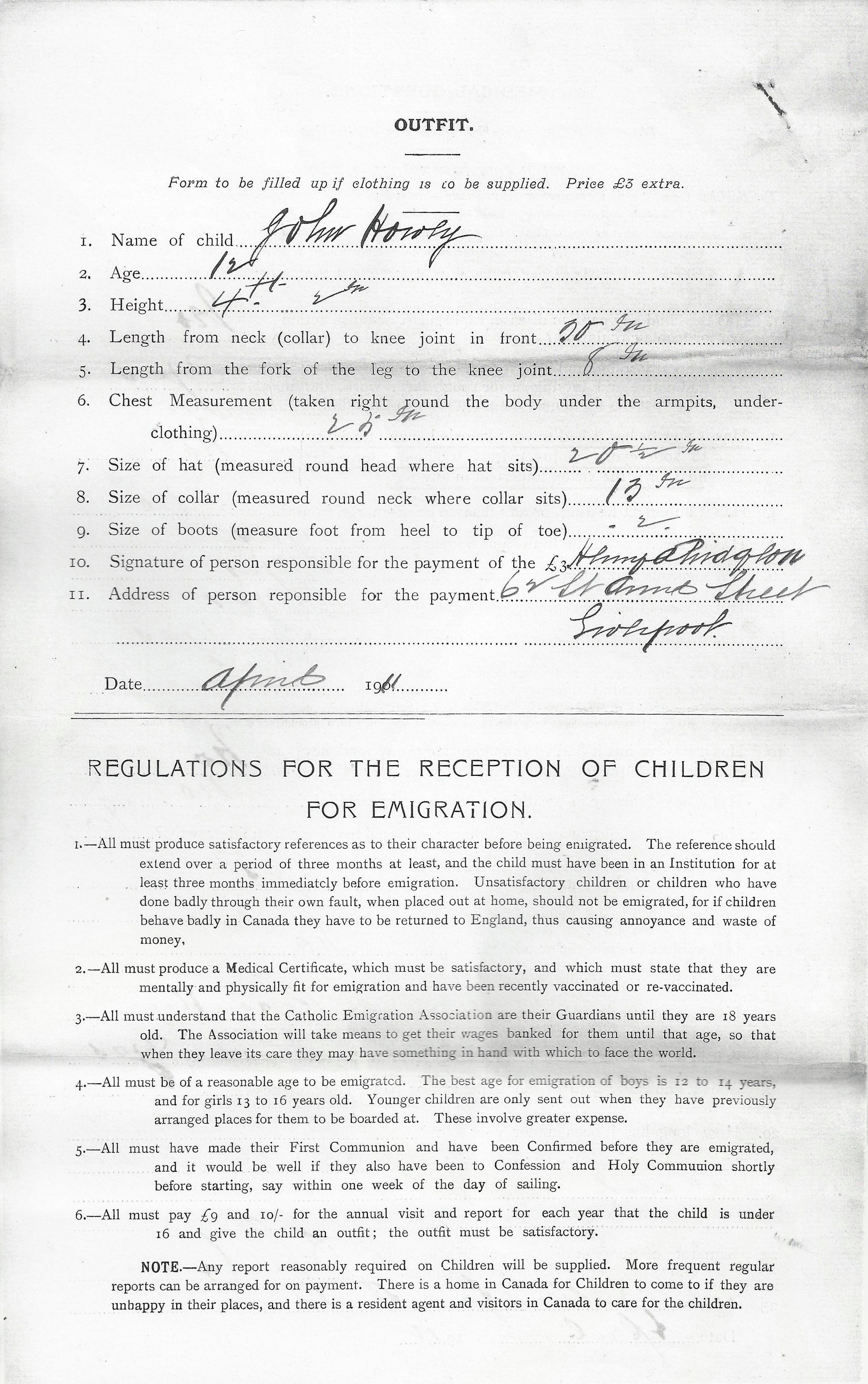

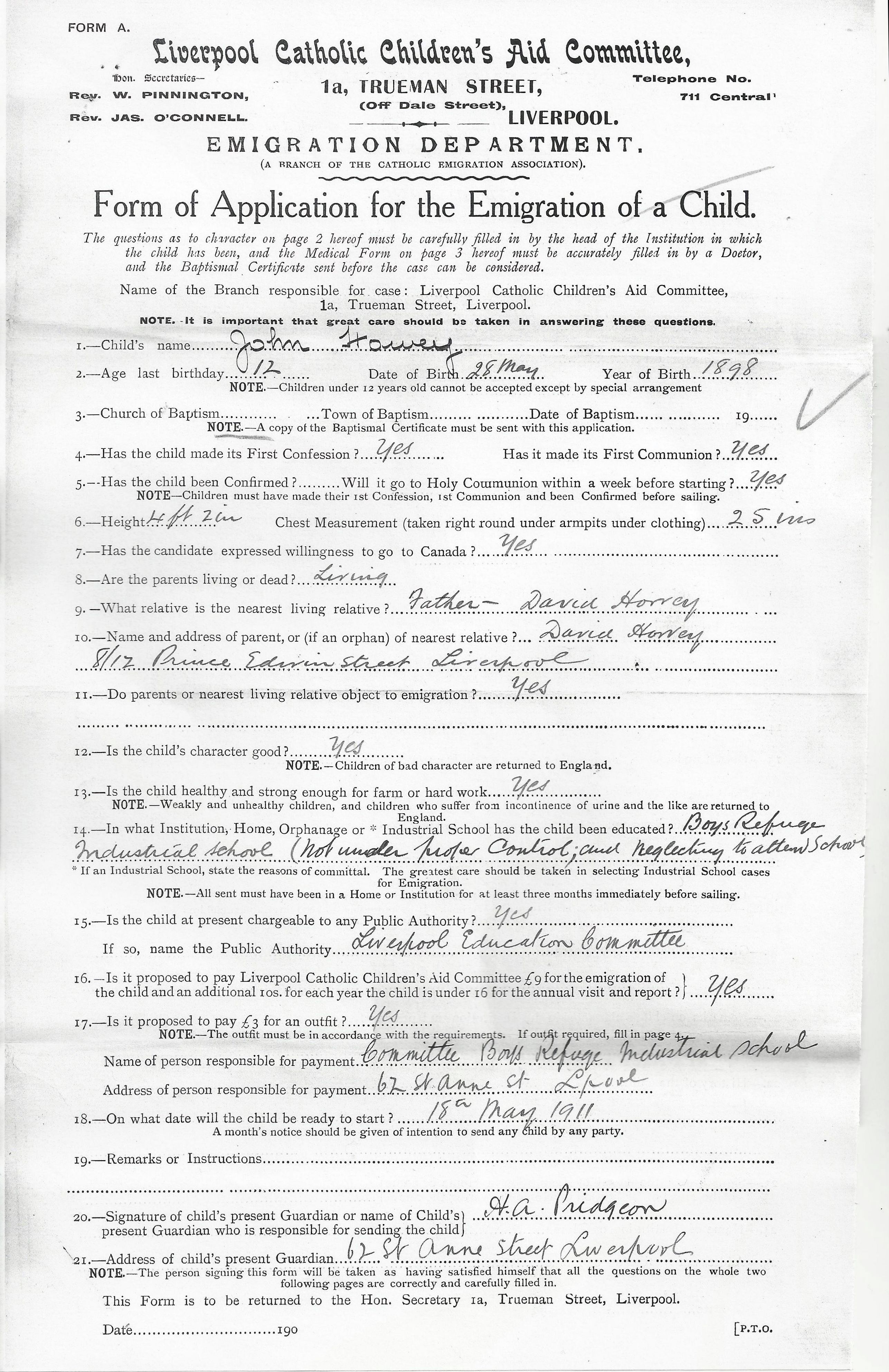

At the age of twelve, John’s life took a dramatic turn when he was selected for emigration to Canada under the British Home Children programme.

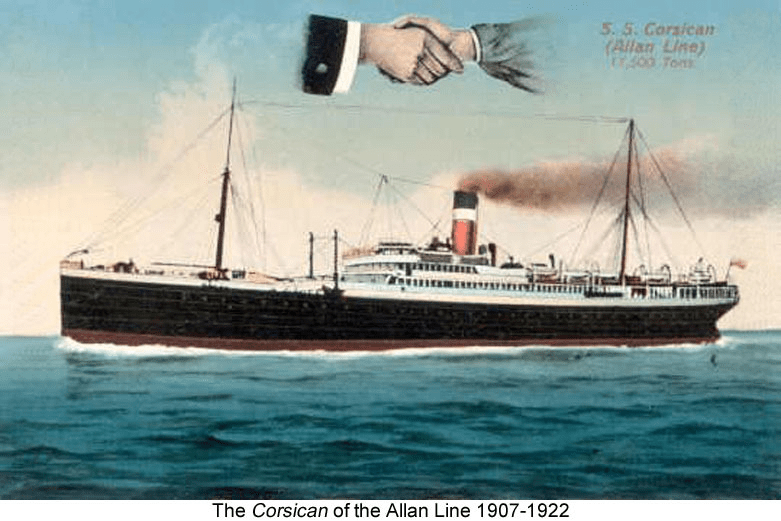

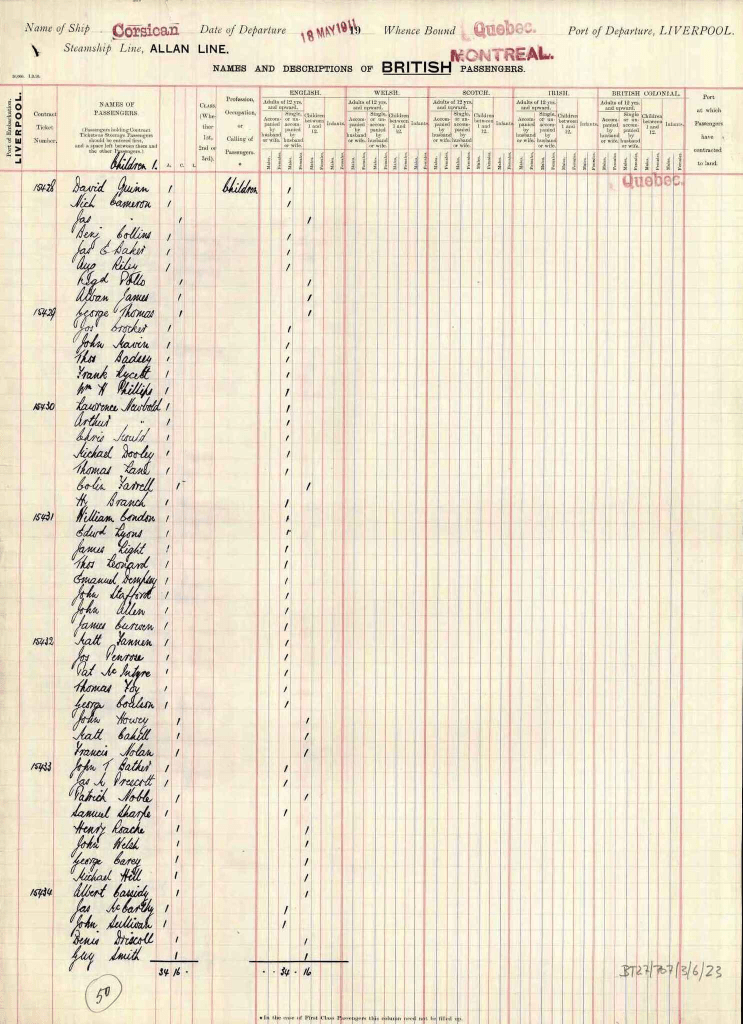

On 18 May 1911, just ten days before his thirteenth birthday, John departed Liverpool aboard the RMS Corsican as part of a group sent by the Catholic Emigration Association. The Catholic Emigration Association, which operated homes in Liverpool and Canada, was one of over 50 organizations that facilitated the migration of more than 100,000 British children to Canada between 1869 and 1948.

These children, euphemistically called “Home Children,” were predominantly from disadvantaged backgrounds—some were orphans, but many, like John, came from institutional care or had living parents who were unable to care for them due to financial hardship. The organizations coordinating these schemes promoted emigration as offering children a fresh start and better opportunities in Canada’s agricultural economy. In reality, most children were placed as indentured farm laborers or domestic servants, often experiencing exploitation, neglect, and abuse.

Life on Canadian Farms

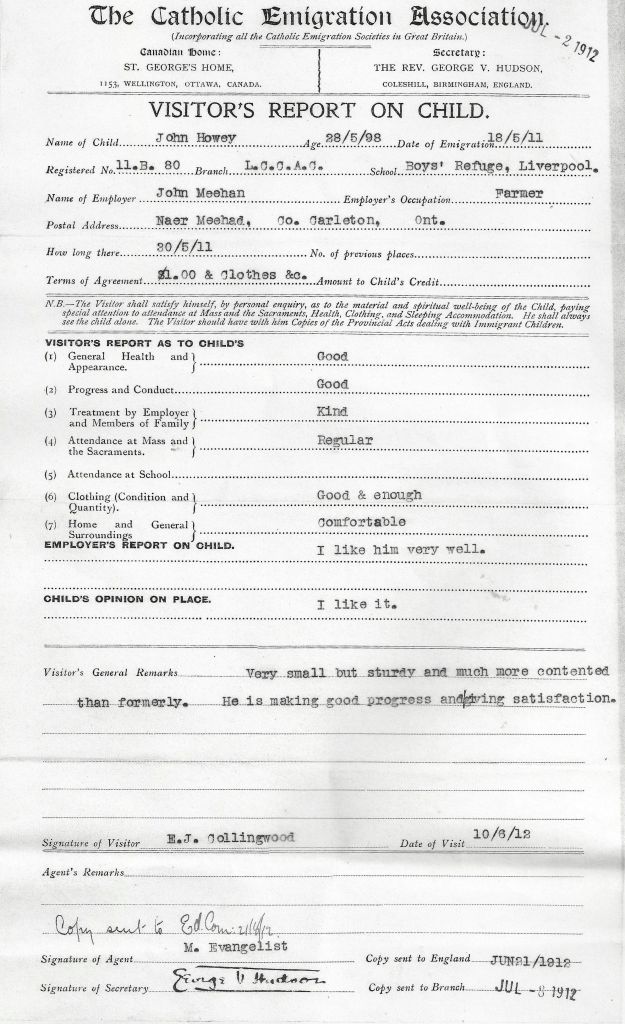

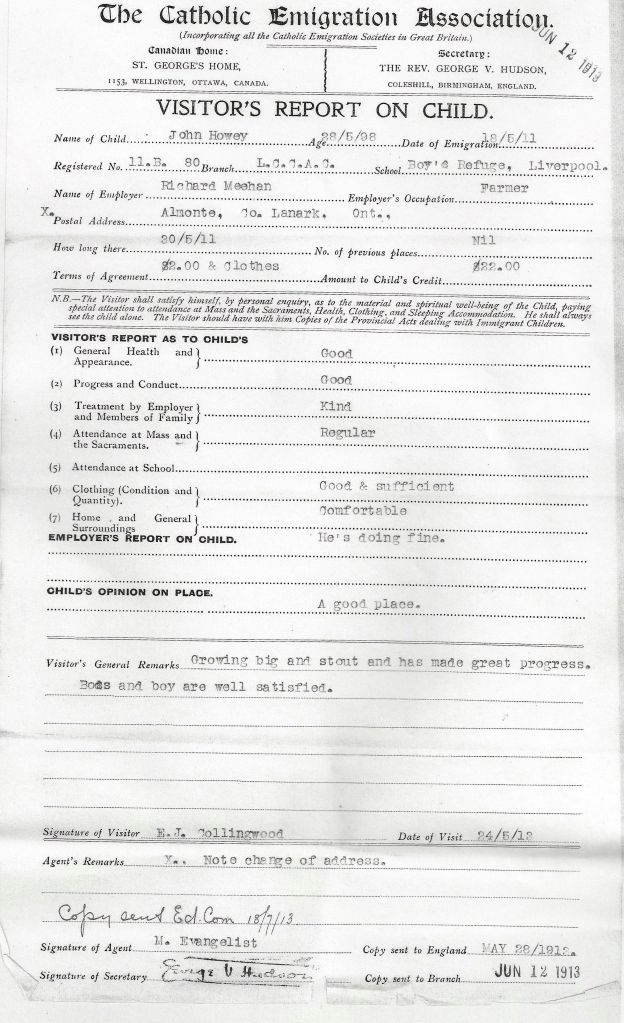

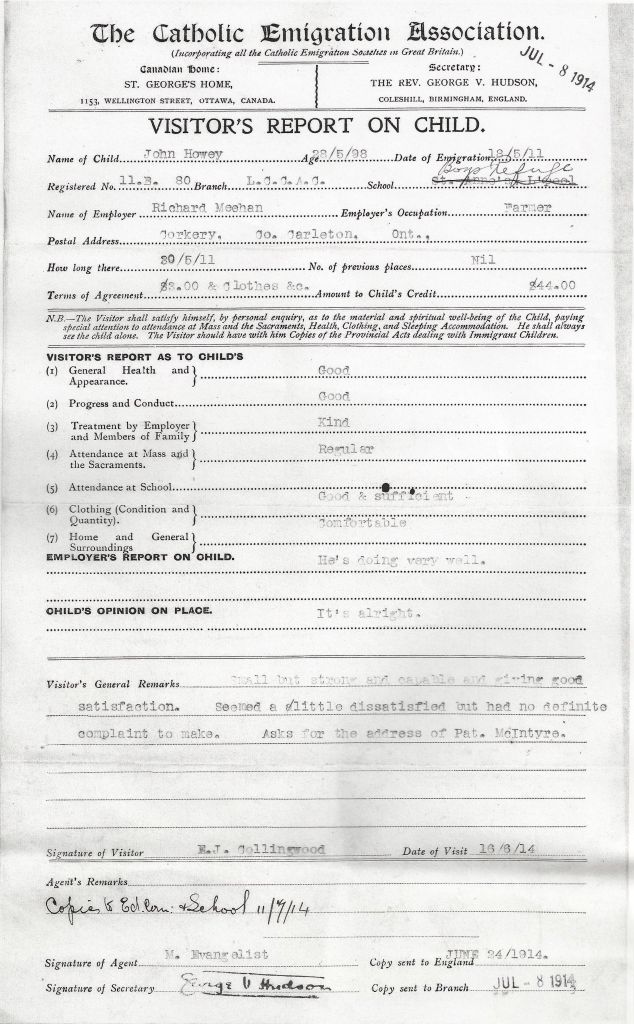

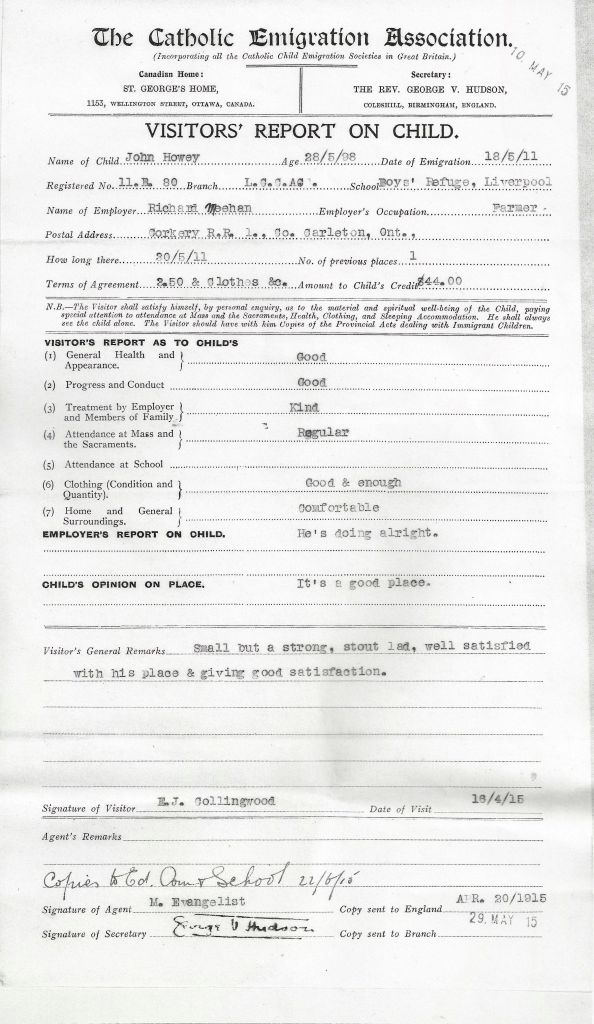

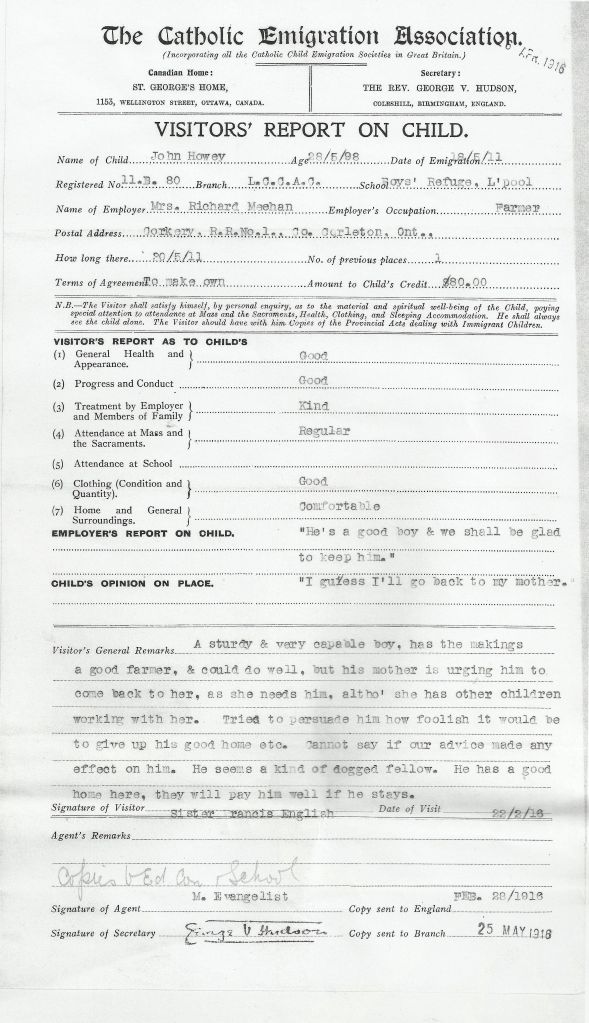

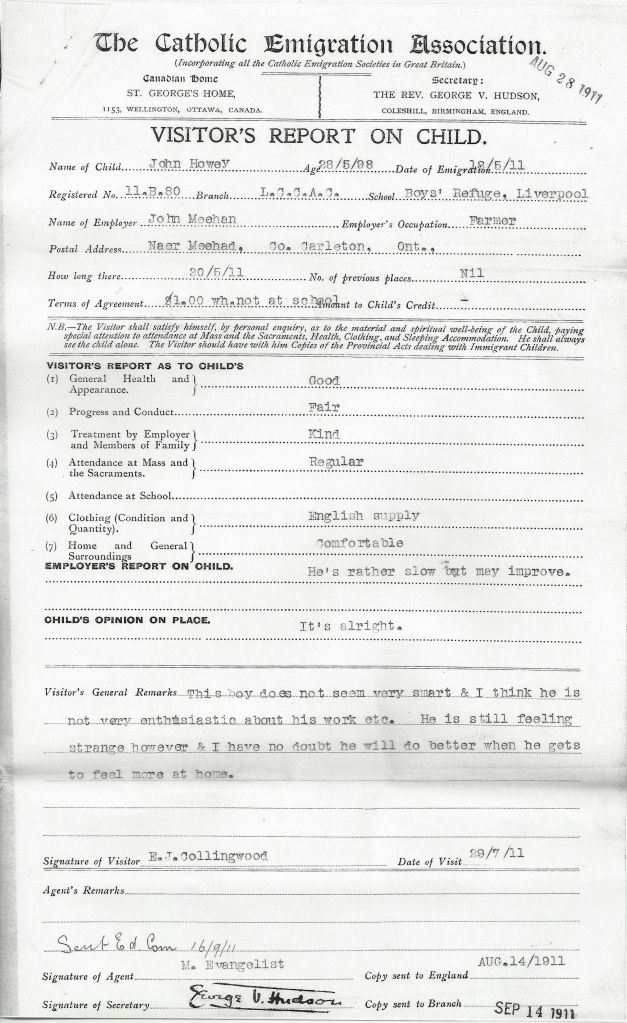

Upon arrival in Canada, John was placed with farming families in Ontario, where he worked as a farm laborer. The visitor reports from the Catholic Emigration Association provide revealing glimpses into his circumstances during these formative years. These inspection reports, conducted by social workers from the Catholic Emigration Association, documented children’s living conditions, treatment by employers, and progress in their placements.

The 1911 visitor report describes John as living at “990 Meehan House” near Meehed, working for John Meehan, a farmer. The visitor noted that John “does not seem very smart & I think he is not very enthusiastic about his work etc. He is still feeling strange however & I have no doubt he will do better when he gets to feel more at home”. This assessment captures the profound disorientation and homesickness that many Home Children experienced upon arrival, particularly for a boy who had already endured years of institutionalization in England.

By 1912, a follow-up report indicated modest improvement: “Very small but sturdy and much more contented than formerly. He is making good progress and giving satisfaction”. The report also noted John’s opinion: “I like it,” suggesting some adaptation to farm life. However, a 1916 visitor report painted a more complex picture, describing him as “A sturdy & very capable boy, has the makings [of] a good farmer, & could do well, but his mother is urging him to come back to her, as she needs him, altho’ she has other children working with her”.

This poignant detail—that John’s mother Margaret was actively seeking his return—contradicts the narrative often promoted by emigration societies that families had permanently relinquished their children. Margaret’s pleas for her son to return home reveal that despite the difficulties that led to John’s institutionalization and emigration, maternal bonds remained strong. The visitor’s comment that the organization “tried to persuade him how foolish it would be to give up his good home etc” reveals the paternalistic attitudes of these institutions, which often prioritized keeping children in Canada over family reunification.

The reports consistently describe the treatment John received as “kind” and his living conditions as “comfortable,” with regular church attendance noted. Yet the emphasis on his initial reluctance to embrace farm work and his mother’s pleas for his return suggest an underlying unhappiness that the inspectors either minimized or failed to fully appreciate.

First World War Service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force

Enlistment and the 238th Battalion

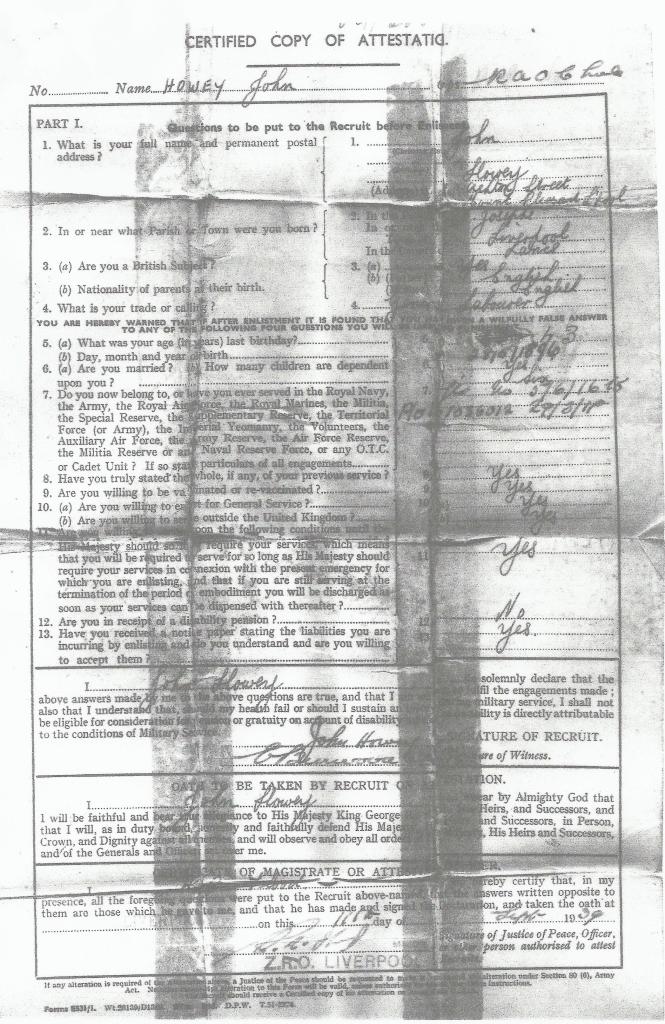

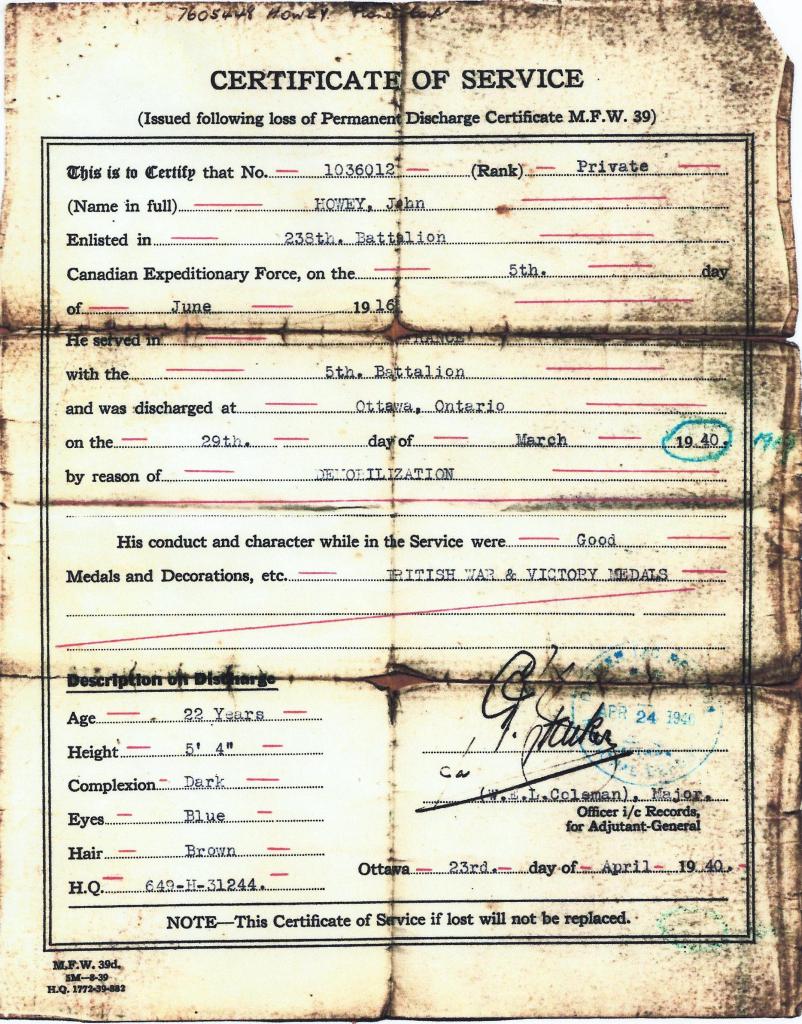

in 1916, John made a decision that would define the next phase of his life: he enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. On 5 June 1916 in Ottawa, Ontario, the seventeen-year-old John (claiming to be eighteen) attested for service with the 238th Infantry Battalion, CEF. His attestation papers provide detailed information about his circumstances at enlistment.

On the attestation form, John listed his next of kin as “David Howey,” his father, residing in South Wales. This suggests that despite his mother Margaret’s active efforts to bring him home, official communication went through his father, possibly reflecting Victorian-era conventions about male authority or indicating that David remained the legal guardian. His stated occupation was “farmer,” reflecting his five years of agricultural work in Canada.

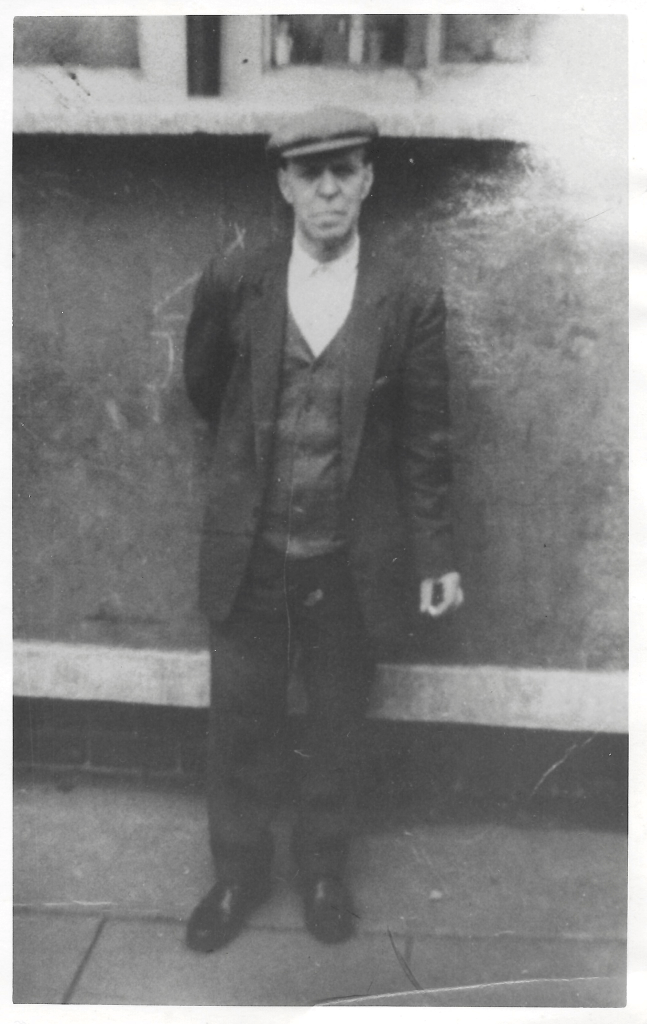

At enlistment, John stood just 5 feet 2 inches tall with a 35-inch chest measurement, had a fair complexion, blue eyes, and brown hair. These physical characteristics suggest he remained small in stature, possibly due to the nutritional deprivations of his childhood in Liverpool and his years in institutional care. His regimental number was 1036012. He listed his religion as Roman Catholic, maintaining the faith in which his mother Margaret had raised him.

The 238th Battalion was a forestry battalion raised in Ontario and Quebec, authorized under General Order 69 in July 1916 with mobilization headquarters at Camp Valcartier. The battalion recruited primarily from rural areas and was intended to provide timber resources crucial to the Allied war effort. Unlike combat infantry battalions, forestry units cut and prepared lumber in the United Kingdom and France for use in constructing trenches, barracks, airfields, and other military infrastructure.

Service in England and Scotland

On 11 September 1916, the 238th Battalion embarked from Halifax, Nova Scotia, aboard a troopship with a strength of 44 officers and 1,082 other ranks. After a nine-day Atlantic crossing, the battalion arrived at Liverpool on 22 September 1916—ironically returning John to his birthplace for the first time since his emigration five years earlier, though likely only briefly as the unit was immediately conveyed by train to Witley Camp in Surrey for training. One can only imagine John’s emotions as his ship docked in the city where his mother Margaret still lived, knowing he might be so close yet possibly unable to see her.

In October 1916, the 238th Battalion was absorbed into the Canadian Forestry Corps and reorganized into forestry companies. Scotland and England were divided into forestry districts, with the former 238th Battalion assigned to No. 52 District (formerly No. 2 District) headquartered at Orton Park near Carlisle under Lieutenant-Colonel W.R. Smyth. Detachments operated at various locations including Dalston near Carlisle, Riddings Junction on the Netherby Estate, Castle Douglas in Scotland, and Whittingham in Northumberland.

The forestry companies specialized in different types of timber: the 238th concentrated primarily on cutting pine, while other battalions focused on beech or spruce. Some companies were also engaged in quarrying stone and constructing airfields for the Royal Air Force. The work was physically demanding and dangerous, though less immediately life-threatening than front-line infantry service.

John’s specific assignments within the Canadian Forestry Corps are not detailed in the available records, but his five years of farm labor in Canada would have made him well-suited to the heavy manual work of logging operations. Many British Home Children who enlisted saw military service as an opportunity for adventure, escape from their constrained circumstances, and a chance to prove their worth. An estimated 10,000 former Home Children served in World War I, representing nearly all those of eligible age.

Return to Britain

John remained with the Canadian Forestry Corps until the war’s end and the subsequent demobilization. According to the 1920 Canadian Expeditionary Force document, John sailed back to Liverpool on 7 June 1920. At twenty-two years old, he had spent nine years away from his birthplace—more than half his life at that point—and could finally be reunited with his mother Margaret and whatever remained of his family in Liverpool.

Post-War Life, Family, and the Long Road to Marriage

Reunion with Gladys Gray

Shortly after returning to Liverpool, John met Gladys Rosa Lillian Gray, a young woman from Holbeach, Lincolnshire, born on 6 July 1905. Gladys was the daughter of Robert Gray, a farm worker, and Violet King. In December 1924, when Gladys was nineteen, she married Leonard Charles Osborne in Holbeach. The couple had two daughters: Joyce Margaret (1925) and Mary Rose Irene (1927).

At some point in the late 1920s, Gladys’s marriage to Leonard Osborne apparently faltered, and she began a relationship with John Howey. The exact circumstances of how they met and when their relationship began remain unclear, but by 1930, Gladys and John were living together and would go on to have six children over the next eighteen years:

- Muriel (.1930)

- Constance (1932)

- John (1937)

- Shirley (c.1937)

- David (1940)

- [Living] (born 1948)

The Marriage Delay: Divorce and Social Stigma

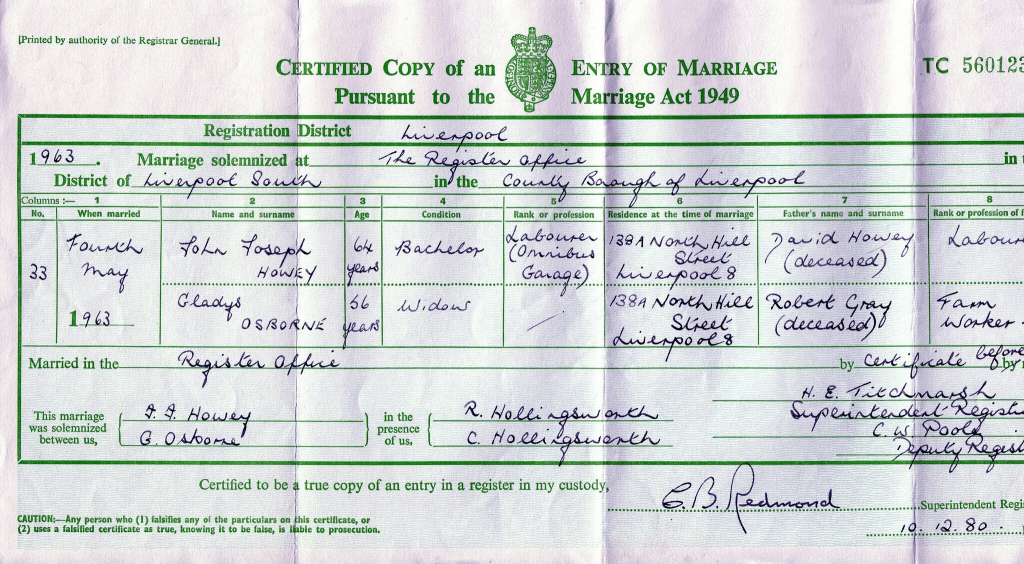

Despite living as a family for more than three decades and raising six children together, John and Gladys did not marry until 4 May 1963, when John was 64 and Gladys was 57. This extraordinary delay of more than 35 years was almost certainly due to Gladys’s existing marriage to Leonard Osborne. In mid-twentieth-century Britain, divorce carried significant social stigma, particularly within Catholic communities like the one in which John had been raised by his mother Margaret.

The fact that Gladys and John finally married in 1963 strongly suggests that Leonard Osborne died sometime before that date, making Gladys a widow and free to remarry. Their marriage took place at the Liverpool South Registry Office—a civil ceremony rather than a church wedding, which would have been impossible given the Catholic Church’s prohibition on remarriage after divorce. The witnesses were their daughter Constance Hollingsworth (née Howey) and her husband Ronald Hollingsworth, underscoring the family’s support for finally formalizing the union.

On the marriage certificate, Gladys’s father Robert Gray was listed as deceased and identified as a farm worker. John’s occupation was recorded as a labourer, reflecting his working-class status throughout his adult life.

Second World War Service with the Pioneer Corps

Re-Enlistment at Age 41

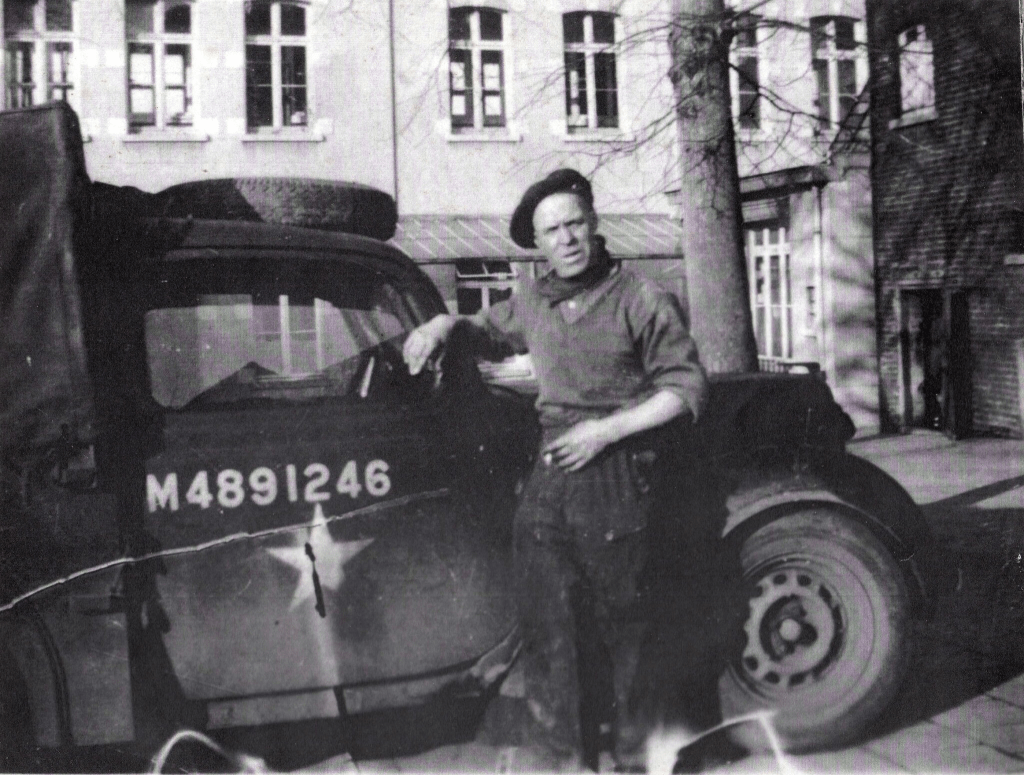

When Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, John Howey—now a 41-year-old father of five, with a sixth child yet to come—once again answered his country’s call to arms. On 11 September 1939, just eight days after the declaration of war, John enlisted at Liverpool in the 324 Company, Pioneer Corps. His service number was 4605448.

The Pioneer Corps (originally the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps) was a non-combatant service that performed essential manual labor for the British Army. Pioneer companies worked at ports, railheads, and bases loading and unloading supplies; constructed and repaired roads, railways, and airfields; cleared debris from bomb sites; and produced smoke screens to protect strategic locations from air raids. During the London Blitz, over fifty Pioneer Corps companies served in the capital, clearing rubble, demolishing damaged buildings, keeping roads open, and rescuing survivors—dangerous work that resulted in more than one hundred Pioneer Corps soldiers being killed or seriously wounded.

Military Service Record

John’s Soldier’s Service Book and Release Book provide detailed information about his Second World War service. His description on enlistment recorded his date of birth as 28 May 1898, making him 41 years old. He stood 5 feet 5 inches tall—three inches taller than his WWI enlistment height—and weighed 118 pounds, with a fresh complexion, brown hair, and blue eyes. A distinctive mark noted was a “tattoo on forearm“. His religious denomination was listed as Roman Catholic, the faith his mother Margaret had instilled in him.

Unlike his World War I service, John did not serve overseas during the Second World War. His service appears to have been primarily in England, performing labor duties with the Pioneer Corps. His conduct was assessed as “Very Good,” and he was described as a “dependable and willing NCO” who could “turn his hand successfully to various jobs” and was “a useful NCO, showing understanding and training”. These assessments suggest he earned the respect of his superiors and performed his duties competently.

Demobilization

John was demobilized on 14 July 1945 at the Military Dispersal Unit in Shorncliffe, Kent. His Soldier’s Release Book indicates he was released as a Lance Corporal (L/Cpl), suggesting he had been promoted during his service. He was entitled to war gratuity and post-war credits, which were deposited in the Post Office Savings Bank. The release book also contained information about medical benefits, dental treatment, and instructions for claiming disability pensions if needed.

By the time of his demobilization, John had served for nearly six years and was 47 years old. He returned to Liverpool and to Gladys and their children, including their youngest, Brenda, who had been born in February 1948 during the post-war period.

Final Years and Legacy

After demobilization, John spent the remaining twenty-two years of his life in Liverpool, working as a labourer to support his large family. The post-war years in Britain were characterized by austerity, rationing, and economic hardship, and working-class families like the Howey’s faced ongoing challenges. Nevertheless, John and Gladys maintained their household and raised their children through these difficult decades.

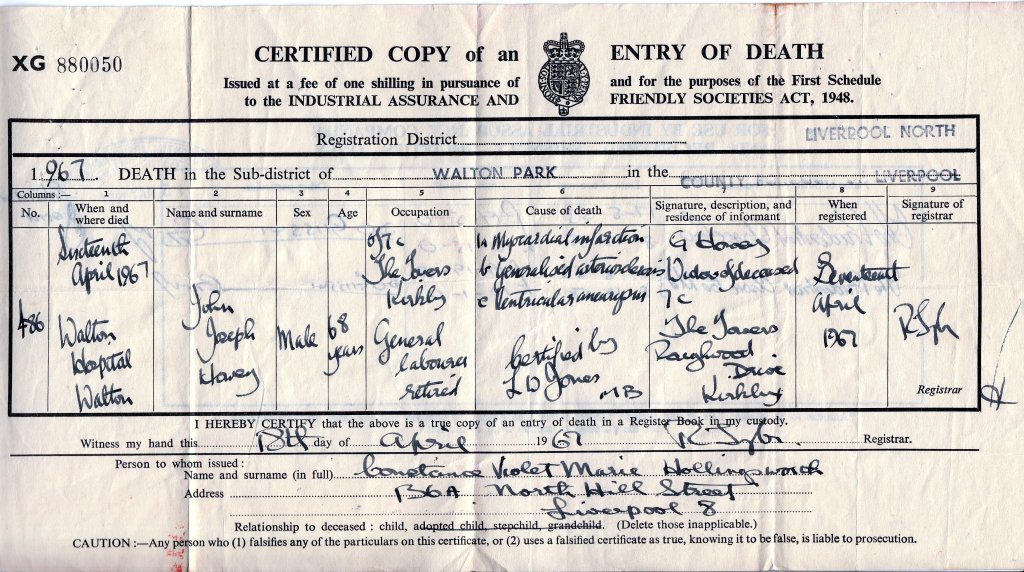

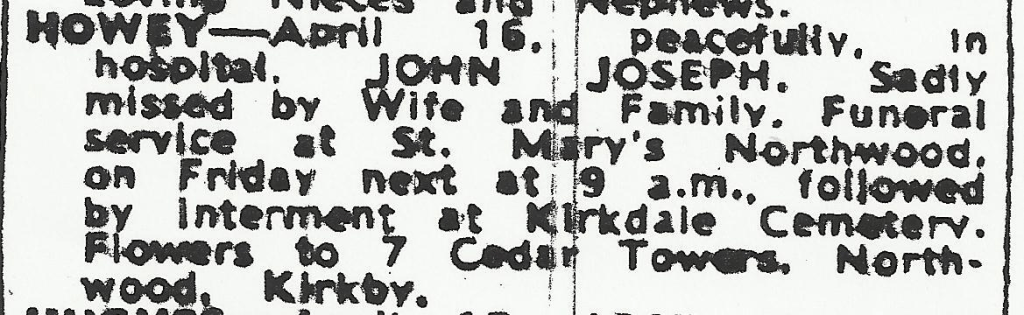

In 1963, after more than three decades together, John and Gladys were finally able to marry, giving legal recognition to their long-standing partnership. Tragically, their married life would be brief. On 16 April 1967, John Joseph Howey died of a heart attack at the age of 68 in Liverpool. He was buried five days later, on 21 April 1967.

John’s widow, Gladys, survived him by twelve years, dying on 19 September 1979 at age 74 in Liverpool from cardiorespiratory failure, including bronchopneumonia, chronic bronchitis, and hemiplegia. They left behind a large extended family: their six children together, plus Gladys’s two daughters from her first marriage, numerous grandchildren, and eventually great-grandchildren who carry forward their legacy.

Conclusion: A Life of Service and Resilience

John Joseph Howey’s life trajectory exemplifies the experiences of countless working-class individuals whose lives were shaped by the major historical forces of the twentieth century: poverty, juvenile justice failures, imperial child migration schemes, industrialized warfare, economic hardship, and social transformation. Born in Liverpool to David Howey and Margaret Irwin, institutionalized at ten years old, sent to Canada as a child labourer, serving in two world wars, and raising a large family through decades of austerity, John demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability.

His story also illuminates the darker aspects of British and Canadian history. The British Home Children programme, while promoted as philanthropic, subjected vulnerable children to exploitation, family separation, and psychological trauma. The visitor reports documenting John’s time in Canada reveal an institutional system more concerned with retaining child laborers than supporting family reunification with his mother Margaret. Yet John survived this experience and went on to serve with distinction in both world wars, earning the praise of his commanding officers.

Perhaps most poignantly, John’s personal life reveals the intersection of social stigma, religious doctrine, and economic hardship in mid-twentieth-century Britain. His inability to marry Gladys for more than three decades—despite their loving partnership and six children—underscores the rigid social and legal constraints that governed working-class lives. That they finally married in 1963, less than four years before his death, is both a testament to their enduring commitment and a reminder of the obstacles they faced.

Today, an estimated 12% of Canadians—approximately four million people—are descendants of British Home Children. In Britain, formal recognition of this history came slowly: Prime Minister Gordon Brown issued an official apology in 2010 for the suffering endured by child migrants. Canada established British Home Child Day (28 September) to commemorate these immigrants, though the Canadian government initially resisted apologizing.

John Joseph Howey’s life, meticulously documented in baptismal certificates, visitor reports, military attestation papers, census records, and release books, stands as a powerful testament to the experiences of ordinary people navigating extraordinary circumstances. His story—shaped by his parents David and Margaret, his troubled childhood, his years of forced labor in Canada, his military service, and his lifelong partnership with Gladys—deserves to be remembered not only by his descendants but as part of the broader tapestry of British and Canadian social history.

Hi Ann-Marie, I’m genuinely sorry that this has upset you. The site is very much a work in progress and…

This is disgusting, as a part of this family it’s incredibly inaccurate. Very jaded and entirely inappropriate you have not…

Leave a comment